Apple’s M series chips were incredibly well telegraphed when they arrived in late 2021. Apple had been designing its own silicon since the A4 appeared in the iPhone 4 just over a decade earlier. The appearance of Apple’s in-house efforts in the Mac was really just a question of when, not if.

When the M1 came, it landed with a resonating bang. In addition to being genuinely noticeably faster, the chips were seen as a big step forward for portable computing because of their shockingly improved “performance per watt” that allowed for full-speed processing while on battery power with increased usage times.

Apple has just launched the next iteration of the M line with this year’s M2 MacBook Pro and Mac mini models — officially denoting this as an ongoing series rather than a one-off leap. With confirmed 20% improvements in CPU and 30% in GPU performance in under 2 years and a really aggressive entry price point, the M2 adds to Apple’s lead in portable chipsets.

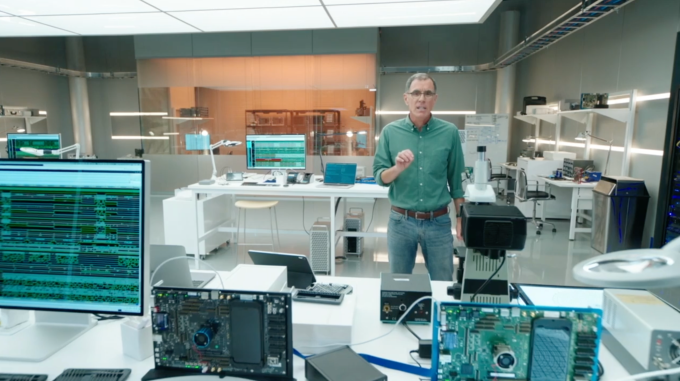

I was able to spend a bit of time talking to Apple’s vice president of Platform Architecture and Hardware Technologies Tim Millet, as well as VP of Worldwide Product Marketing Bob Borchers about the impact of the M chips so far, how they see the line developing over time and a bit about gaming too.

Resetting the baseline

“A lot of it comes down to the people and the talent on Tim’s team,” says Borchers, “but I think a lot of it also comes down to the way that we’ve approached designing Apple silicon from the very beginning.”

Millet has been building chips for 30 years and has been at Apple for nearly 17. He says that with M1, Apple saw an opportunity to “really hit it.”

“The opportunity we had with M1 the way I looked at it, it was about resetting the baseline.”

When their desktop computing and laptop computing pipeline was essentially controlled by the third-party merchants and silicon vendors, it didn’t really allow for Apple to push the bar closer to the limits of technology.

This need to own and “reset” the baseline of portable performance in computing coalesced around the time that Apple started working on the iPad Pro. They had been building chips inside of these super-thin enclosures and knew that, with ready power and much larger casings, they could make a significant impact on portable computing.

“Once we started getting to the iPad Pro space, we realized that ‘you know what, there is something there.’ We never, in building the chips for iOS devices, left anything on the table. But we realized that these chips inside these other enclosures could actually make a meaningful difference from a performance perspective. And so with M1 we were super excited about the opportunity to have that big impact — shifting all of it back up to redefining what it meant to have a laptop in many different ways.”

The work that Apple did with the M1 wasn’t focused on pure peak performance, says Millet. From the beginning, there was this idea that they’d be able to reset user expectations around what kind of performance you should be able to get out of a portable computer, and for how long. The focus on performance per watt paid off (as noted in my early review of Apple’s first M1 chip), in that people could run major compute tasks on laptops untethered from power for hours. No compromises. That, says Millet, wasn’t a byproduct — it was the intent from the beginning.

“We wanted to have the ability to build a scale of solutions that deliver the absolute maximum performance for machines that had no fan; for machines that had active cooling systems like our pro class machines. We wanted to…move performance per watt to the point where we delivered real usable performance in these in a wide range of machines.”

Apple vice president of Platform Architecture and Hardware Technologies Tim Millet

Millet says that Apple was pleased with what it had been able to ship with M1 and that it served those goals. My own experiences and those of power-hungry users mirrored that sentiment once the machines began to ship. For decades, Apple had been running up against third-party stewardship over chipset speeds, power requirements and features — with the result of increasingly less mobile computers that ran hot, loud and short. The whole portable industry had been constricting that flexibility for so long that most users (aside from those of us who spend our lives closely examining these boundaries) probably didn’t realize how hard it was for them to breathe.

The M1 whacked a big old reset button on those restrictions, putting portable back into the power computing lexicon. And with M2, Millet says, Apple did not want to milk a few percentage points of gains out of each generation in perpetuity.

“The M2 family was really now about maintaining that leadership position by pushing, again, to the limits of technology. We don’t leave things on the table,” says Millet. “We don’t take a 20% bump and figure out how to spread it over three years…figure out how to eke out incremental gains. We take it all in one year; we just hit it really hard. That’s not what happens in the rest of the industry or historically.”

Borchers chimes in to note that Apple is building products, not parts. This gives it a much tighter loop between needs and deliverables. He notes that the pairing of the technology and product is not an independent choice at Apple; it’s silicon, software and hardware coming together, starting at the point of inception. It’s not “Can we do this?” and then waiting to see if a vendor can deliver the appropriate capability.

“As somebody who’s been building silicon for 30-plus years, the luxury of knowing what the target is, and working side by side with the product designers, the hardware system team, the software people to understand exactly what you’re aiming at, makes all the difference in our ability to really target and make sure we’re adding things that matter, not adding anything that doesn’t,” Millet agrees.

Forcing functions and forgetting fans

For much of the modern history of the Mac, after Apple moved from PowerPC to x86 in 2006, it has had less immediate control over capability in its machines. Whatever it hoped to accomplish with a new machine, it had to include an external factor in there, with external partners like Intel delivering on their own timelines and complexities. There was a forcing function in place. That partner is telling you, “This is what we can deliver you on your scale in this timeframe for these applications,” which cascades all the way through to product design and development.

Apple retaking control of its silicon pipeline also reset the size and complexity of that development feedback loop, which prompts me to ask them whether that relationship has changed internally at Apple post-M1.

“If you go back to the phone, we had that tight interaction really, from the very beginning — and I think that’s true for all of the iOS products. We had that tight feedback loop,” says Millet.

Both Millet and Borchers are diplomatic about the Intel partnership (which is till present, for now, in Apple’s Mac Pro machines).

“Intel was a great partner through the years where we shipped the Intel machines. They were very responsive; they really actually were inspired by the direction that Apple pushed them. And I think our products benefited from that interaction. Of course, our competitors’ products benefited from that interaction as well sometimes,” notes Millet.

But, undoubtedly, the relationship between what Apple wants to ship and what it can ship has been radically altered now that the M-series chips are in the breadth of its lineup. Apple’s chip team working closely with internal teams has been a natural part of Apple’s device pipeline since it began work on the iPhone 4. Now that system has expanded to envelop the Mac branch as well.

“I think it felt very natural for us to sit down side by side with our industrial design partners and our system team partners inside Apple because they’re familiar faces to us,” Millet says. “These are people that we’ve been working with for iPad and iPhone. And it really felt very, very natural. It’s a very Apple way of working where we are all sitting at the table together, imagining possibilities and them challenging us and us going back and doing the math to kind of figure out that ‘yeah, I think we can do that without a fan.’”

Borchers sparks on my use of the term “feedback loop” and notes that it’s less that the loop is smaller and instead that it has been eliminated.

“[That term] implies some sense of latency or delay in the cycle,” he says. “And I think that it’s an appropriate way of thinking when you’ve got multiple parties involved. I think that the big difference here is that we move from having a feedback loop to co-creation, where there isn’t a feedback loop…You [just] sit down at a table and push each other. Okay, well, what if we got rid of the fan? And it doesn’t require this latency in the system, which I think has efficiency gains, but it also unleashes your creativity in new ways. So I actually think you hit on something interesting there in kind of this difference between a feedback loop and a different kind of process.”

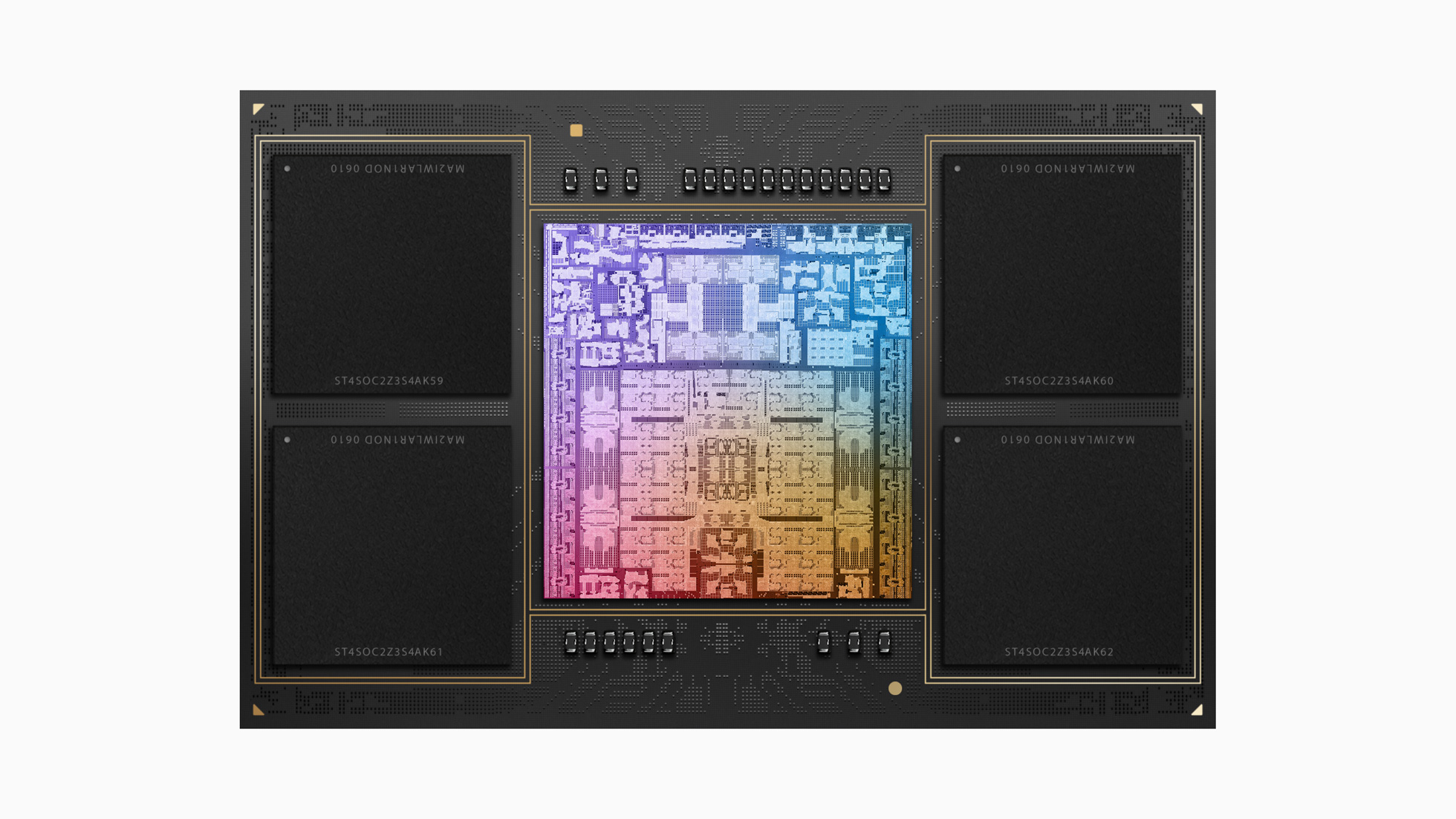

M2 Max features 67 billion transistors, 400GB/s of unified memory bandwidth, and up to 96GB of fast, low-latency unified memory. (Image: Apple)

Gaming on the Mac

One arena still holds fascination for any of us who have found a home on the Mac for nearly every part of our digital life — save one: gaming. The M-series Macs are undoubtedly more gaming capable than any previous Mac due to the inclusion of much-improved onboard GPUs across the lineup. But even with big titles popping up on Mac in spurts, there still is a fairly large section of “here there be dragons,” where you would think Apple would like to map in the multi-billion-dollar gaming market.

Borchers says that Apple is feeling like the Apple silicon gaming story is getting more solid release by release.

“With Capcom bringing Resident Evil across, and other titles starting to come along, I think the AAA community is starting to wake up and understand the opportunity,” he says. “Because what we have now, with our portfolio of M-series Macs, is a set of incredibly performant machines and a growing audience of people who have these incredibly performant systems that can all be addressed with a single code base that is developing over time.

“And we’re adding new APIs in and expanding Metal in Metal 3, etc. And then if you think about the ability to extend that down into iPad, and iPhone as well, I think there’s tremendous opportunity.”

He acknowledges that Apple needs to do work to bring game developers along the road to adoption, but he says the company is happy that they’ve shipped the core ingredients in very performant systems. He says that the team has been and will continue to look at a variety of chip configurations and components through that gaming lens as well. Anyone who games on the Mac should find room for encouragement in the way Millet says that the team is focusing here, though time will tell.

Millet says that Apple’s work on cracking the gaming market started with the early days of the Apple silicon transition.

“The story starts many years ago, when we were imagining this transition. Gamers are a serious bunch. And I don’t think we’re going to fool anybody by saying that overnight we’re going to make Mac a great gaming platform. We’re going to take a long view on this.”

He notes that Apple offers common building blocks that are shared, scaled appropriately, between the Mac, iPhone and iPad where Apple has historical strength. But he also points out that the purpose-built GPUs in the iOS devices weren’t intended to be general use.

“We weren’t going to design GPUs for that space that were unnecessarily complicated, that had features that were not relevant to iOS,” he notes. “But as we looked at the Mac, we realized that this is a different beast. There will be different expectations over time — let’s make sure we have our toolbox complete.

“And so we did very directed work to make sure that the GPU toolbox was there — working super closely with our Metal partners. We worked hand in hand to make sure that they were going to have all the tools that they needed to accelerate the important APIs that we’re going to deliver to [companies like] Capcom, for example. So that when Capcom approached us, it wasn’t going to be this awkward port for them. It was going to be a very natural ‘Ah, you do support these modern APIs that gamers are needing. This is interesting.’”

That, in turn, makes it simpler to approach game developers with a strong set of tools that feel familiar enough and compatible enough with their existing workflows to make porting games or building for the Mac viable.

“My team spends a lot of time thinking about how to make sure that we’re staying on that API curve to make sure that we’re giving Metal what it needs to be a modern gaming API. We know this will take some time. But we’re not at all confused about the opportunity; we see it. And we’re going to make sure we show up.”

He also acknowledges that it will take time to build an installed base of strong GPUs in order for it to be enticing to the AAA space.

“The other thing we wanted to do, and I think we have hopefully done, is to seed the Mac, the full Mac lineup, with very capable GPUs, whether it be the MacBook Air, obviously, all the way up to the beast, Ultra chips that we can put in our Mac Studio.”

“Because until you do that, until you have a population distributed, developers are going to be wary about making a big investment and kind of focus on Mac,” Millet acknowledges.

So Apple will continue to seed the Mac population as people upgrade from Intel to M1 or M2, and it will, hopefully, become more and more obvious to developers that the Mac population at large has a machine that is capable of running major titles at a frame rate that is acceptable to gamers.

Millet also is unconvinced that the game dev universe has adapted to the unique architecture of the M-series chips quite yet, especially the unified memory pool.

“Game developers have never seen 96 gigabytes of graphics memory available to them now, on the M2 Max. I think they’re trying to get their heads around it, because the possibilities are unusual. They’re used to working in much smaller footprints of video memory. So I think that’s another place where we’re going to have an interesting opportunity to inspire developers to go beyond what they’ve been able to do before.”

The custom technologies of M2 Pro and M2 Max include Apple’s next-generation, 16-core Neural Engine and new powerful, efficient media engines with hardware-accelerated H.264, HEVC, and ProRes video encode and decode. (Image: Apple)

When computer?

Historically, the most vibrant chatter about the Mac is about the next Mac. No matter what gains or features Apple delivers with a particular system, the question readers and friends are always hitting me with is, “When is the next one coming, and is it worth waiting for?” Lest you think it’s just happening out here in user land, Millet says that he gets it, too.

“Friends and family reach out all the time and they say, ‘Hey, I’m thinking about getting a new Mac, wink, wink. Is now a good time?’ And what’s beautiful about this story is that I really, with full sincerity, believe now is always a good time…Nobody should be shy about it.”

Apple has managed to find a sweet spot that allows the bulk of customers to “buy whenever,” knowing that the M-series chips are indeed that good. Millet says that Apple knows that the top few percent of power-hungry users that want the edge on capability are savvy enough to know the rough release timeline of the “new Macs” and will wait for it.

“That 20% is going to make a big difference to some folks. Absolutely. And they will wait for that moment [when] they can see it because they have workloads that require it,” Millet says, while noting that they’re confident enough in the satisfaction levels of buyers of M1 that they’re not going to hold off.

“If you bought a MacBook Pro last year with M1, you’re gonna be fine. [Even] if you bought it in December, you’re not going to come screaming at me telling me I hate this machine, [and] why didn’t you tell me to wait?”

One rationale for shipping M2 is also that Apple wanted to establish the line in a regular cadence. It was important, Millet says, to make sure people didn’t see the M1 as a “one and done.”

As far as the “when Macs” question goes, Millet and Borchers are both in the “when possible, ship” camp. Coming out of a period pre-M1, when many in the Mac ecosystem felt that it was being underinvested in, it’s clear that Apple wants to send a message that this is not the case and they never want that to become a meme again.

“As a silicon person, I know that technology moves fast and I don’t want to wait around. I certainly want to push hard, as you can imagine,” says Millet. “We want to get the technology into the hands of our system team as soon as possible, in the hands of our customer as soon as possible. We don’t want to leave them wondering…do they not care about us? A new phone shipped last year. Why didn’t the Mac get the love?”

“We want to reset to the technology curve and then we want to live on it. We don’t want the Mac to stray too far away from it.”

Borchers says that the opportunity for Apple lies in the fact that the vast majority of Mac customers are on Intel machines. This makes it less of an “it’s been a year, we have to ship something” situation.

“We’re just trying to make it more and more of an easy decision to move…to an even more amazing system,” he says.

When positioned year over year, the gains are absolutely solid. But if Apple is marketing to, and eyeballing the opportunity of, millions of current Intel Mac users, then the calculus (for them) becomes easier. As proud as the team is of the M1 to M2 speed jump, Borchers says, the real messaging is around the leap from just 2 years ago — especially for the Mac mini, where the leaps are in the 10x and up multiples of performance. All in a price that’s $100 cheaper than the M1 Mac mini and $200 cheaper for students.

“We’re product people at the end of the day, and we want to put our systems in as many hands as possible,” says Borchers. “We feel like the Mac mini form factor is such a great way to unleash creativity and, frankly, goodness in the world that we wanted to be able to put it in as many people’s hands as possible.

“We don’t think about [Mac pricing] in a traditional kind of cookie-cutter way where it’s like, ‘Okay, it’s 2023, we’re going to $799 and we’re going to be predictable.’ It’s more of what do we have [in the pipeline], and what can we do that will surprise and delight our customers?”

Apple execs on M2 chips, winning gamers and when to buy a Mac by Matthew Panzarino originally published on TechCrunch

English (US) ·

English (US) ·