I’ve yet to walk the entire floor at Mobile World Congress in Barcelona this year (that’s the goal for this afternoon), but my sense is the majority of the robots present fit into one of two categories: robot vacuums or greeter robots. With Pepper out of commission, maybe there’s a wide-open market there. Who knows?

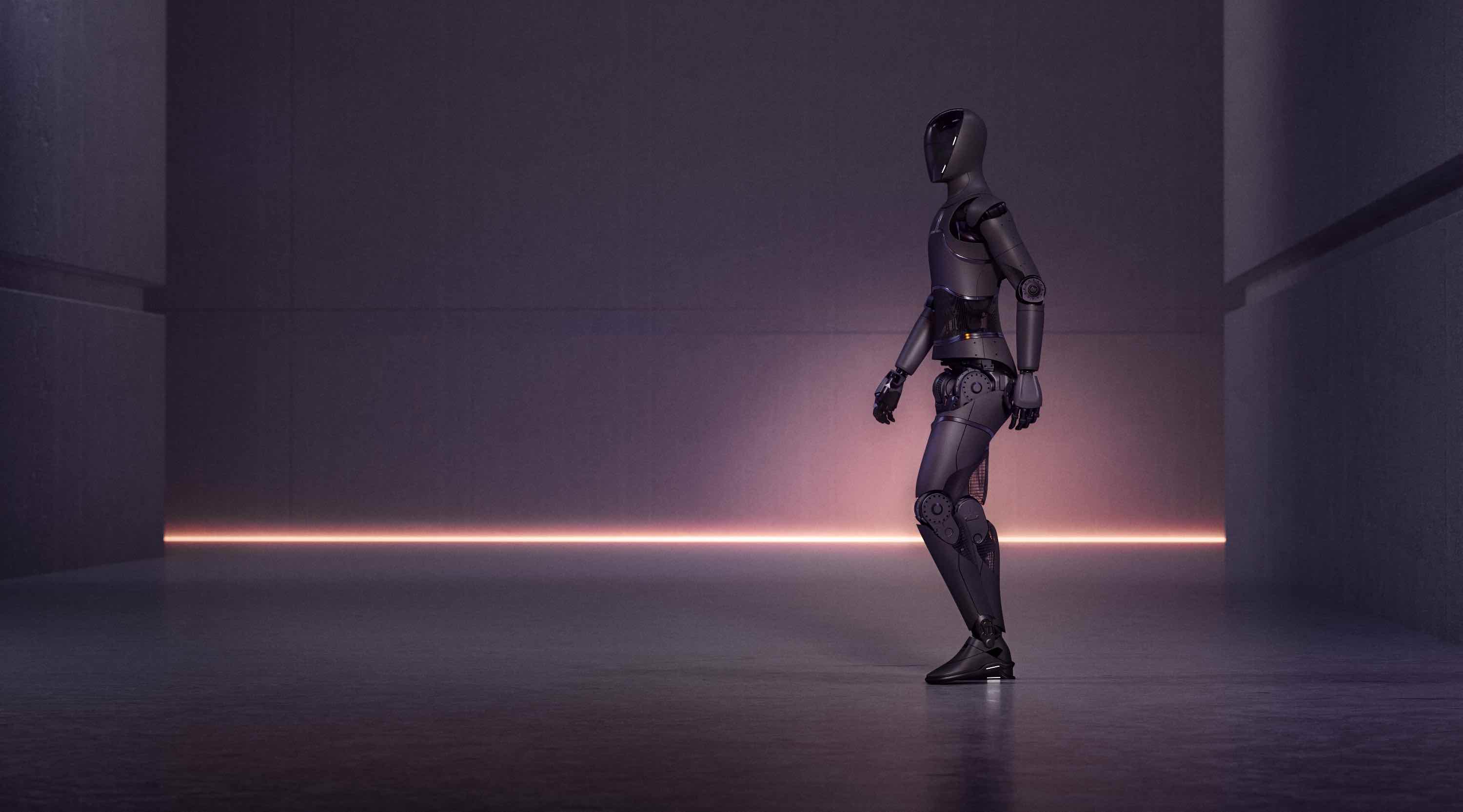

The two Xiaomi robots — CyberOne and CyberDog — may well have been the most prominent of the show, and neither were especially inspiring. It was fun finally seeing the Cyber One in person after writing about it seven months ago. The humanoid robot’s stilted locomotion screamed “research prototype” in the first demo, and I’m plenty wary about phone makers getting “serious” about robotics. There was no demo in the booth this year, rendering it more of an expensive mechanical mannequin.

Xiaomi’s humanoid CyberOne robot at MWC 2023. Image Credits: Brian Heater

CyberDog was moving, at least. The system was significantly smaller than I’d anticipated, standing at only 1.3 feet. The demo largely consisted of some pacing and sitting up and begging. If it’s a toy, it’s an expensive one, at $1,600. It also has some fairly sophisticated hardware on board. It’s powered by Nvidia Jetson and sports an Intel RealSense depth sensor on the front. The quadrupedal dog robotic form factor is a familiar one by now, thanks in no small part to Boston Dynamics’ Spot.

I recently spoke to Boston Dynamics’ founder, Marc Raibert, as part of the TC City Spotlight: Boston event. Since I last had the opportunity to sit down with him, Raibert’s job has changed fairly dramatically. He stepped down from the CEO role a couple of years back, as Boston Dynamics has become much more aggressive about monetizing their products, Spot and Stretch.

Image Credits: TechCrunch

In August, Boston Dynamics’ parent company, Hyundai, announced the launch of the Boston Dynamics AI Institute, with Raibert at the helm. While acting as a corporate research wing, the institute’s research is not currently driven by the same need to productize as Boston Dynamics, the company. For those who missed the live conversation, here’s a transcript of our chat:

TC: The obviously geographical limitations of the name aside, was it clear from the earliest days that Boston Dynamics was always going to stay in the Boston area?

MR: I’m kind of a lifelong Boston person.

I grew up in New Jersey, but my mother grew up here, so I had a connection to Boston from a very early age. I love Boston. I went to school here, left for 10 years, and eventually was faculty at MIT. I was a professor there for 10 years before starting Boston Dynamics. When we started, it was half-time Boston Dynamics, half-time MIT. It wasn’t really motivated by Boston being a hub of robotics. It was just where I was comfortable. We did open a California office.

That was the result of an acquisition?

It was a result of our acquisition of Kinema, which was in Palo Alto when we first got them. And then we opened an office in Mountain View, which is still there.

I didn’t know you’d left Boston for 10 years. What did you do in the meantime?

Three years at the Jet Propulsion Lab, back in the 1970s. And then six years at Carnegie Mellon, on the faculty in both the Robotics Institute and the computer science department.

Were there a lot of robotic applications for JPL in the ’70s?

It was fledgling, but they had a mockup of a Mars rover back in the ’70s. It looked like a car, and it had the old Stanford arms that had a sliding joint. It had some cameras, and there were a couple of different groups working on it.

Image Credits: Boston Dynamics

People talk a lot about brain drain. How large of a problem was the exodus to places like San Francisco and New York in the early days?

I don’t think we’ve lost too many people to the West Coast. Sometimes that happens. When we were part of Google, there was a group of us from Boston Dynamics who moved out to the West Coast, and I think those people mostly stayed. When we got out of Google, they didn’t come back with us. But Boston has its own charms and attraction, and there’s lots of tech here. Lots of schools doing good stuff.

How dramatically has Boston and the Boston ecosystem changed in the 30-plus years since the company was founded?

I don’t know how many startups there are in the area. There’s all the logistics companies — there must be a dozen of them — which all have robotics talent at them. There’s the social robot activity — Cynthia Breazeal’s company [Jibo], and others like that. New things are springing up all the time. To be honest, I think more globally. I’m always thinking of us being an international company, now that Boston Dynamics has Spot robots all around the world. There’s about 1,000 of them out there now.

Obviously, there are certain benefits in terms of infrastructure when it comes to running an institute full of roboticists and AI researchers.

The recruiting here is great. Amazon’s got robotics people. Google is right across the street; they don’t exactly have robotics in Boston, but obviously, they have a lot of talent in AI and software. So those are potential employees. There’s a lot of technical people, but we recruit all across the country, and somewhat from Europe. We’ve been seeing applicants from all over.

How has your day to day changed since stepping down from the CEO role?

There was a point at Boston Dynamics where we were clearly turning more commercial. I decided that I wasn’t the right guy to do that. I had also heard a talk by [Lloyd Blankfein], who was the chairman of [Goldman Sachs], and he gave a talk about his decision to step down. He said, you really need to step down when things are going great. If you step down when things are in trouble, then they think you’re a bum and they kicked you out. But if you do it when it’s going great, it’s hard, because things are so much fun. But that’s when you have to do it.

I listened to that and decided he was right. That, plus the fact that we turning to commercialization. I became the chairman and appointed Rob Playter, who had been my right-hand man. He’d been my graduate student at MIT and been with me for 27 years at that point. He became CEO, and I didn’t have enough to do, to be honest. I thought about retiring. I’m old enough to retire.

When Hyundai agreed to fund the institute, I decided I needed to be here every day to work and inspire the others. And it’s been great. It’s just like being back in it, full-bore.

How much of that push toward commercialization or push toward products activation was a result of the Hyundai acquisition?

It really started when we were still at Google. Then we were with SoftBank for four years, and it was just all about the future. It got to be more about what the products were and tightening up the bottom line. I think another force is that Robert Playter has always wanted to commercialize. I’m a research guy. I really want to work on the long-term and make the next generation or the generation after that happen for robots.

Was the AI Institute part of the Hyundai deal from the beginning?

No. After I became chairman and started to get bored, I wrote a proposal that I actually shopped around to a few billionaires, and got someone to agree at a level that wasn’t enough, in my opinion. Then COVID happened, so I slowed down. But after the Hyundai deal was all done, I pitched it internally, and they went for it.

Beyond the obvious $400 million contribution, what is Hyundai’s relationship to the institute?

They’re the only stockholder in the current arrangement. It’s been very collaborative. I talked to some managers involved, and also to [Hyundai’s] chairman on a regular [basis]. He’s a real enthusiast. He’s really leaning into the future [of] software, AI and other high-tech things. EVs are central to Hyundai to HMG.

Is pure research a hard thing to pitch to a multinational automaker?

The institute has only been around since last summer. You never know until later what the staying power is. Right now, my pitch is to avoid products, because products force you into quarterly and annual work. Products force you into all the various needs of all the various customers. They have a lot of good information, but they also take you in lots of directions. If you want to do the vision of what’s going to come next, it has to come from the technical people who are developing it. I proudly say we’re not doing products. No one’s trying to steer me at the moment.

Was the philosophy of avoiding product part of Boston Dynamics’ mission statement at the beginning?

No. We had some software products in the very early days that we actually made money on. In the early days, we were always in the black, because we didn’t have any investors up until Google acquired us 20-something years in. We always had to be making money. A lot of it was contract work, but we also had some software products.

If productization and commercialization aren’t the focus for the institute, what happens to IP and patents that are developed?

We have a multiprong plan. We can do spinouts. For some, spinouts are seen as a way to commercialize. For me, it’s a way to protect the institute from products.

What research opportunities are afforded the institute that you wouldn’t necessarily have in a university setting?

You have a university, which is full of smart people with blue-sky ambitious goals to do new, novel things. And then you have a corporate lab, which has teamwork. They have support from hardware, software, sensor and electronic engineering, and they have schedule and budget discipline. I think of the institute as being right in the middle, having larger scale. We plan to have about 50 people in engineering that support the work of the researchers, in addition to other engineering people in the research groups. We’re trying to make the future happen and solve really the fundamental problems in robotics, not just the features that are needed right now.

Image Credits: Boston Dynamics (Image has been modified)

The concept of a multipurpose humanoid robot comes around every few years. You’ve been involved in one of the more notable examples, the Atlas robot. Does that bipedal form factor ultimately make a lot of sense?

I don’t know. Elon thinks so. That’s interesting. I would rather point at Spot as a general-purpose robot, because we designed it without a particular application in mind. It’s a platform where you can customize it for your use. We have 1,000 of them out there, which are being used in a reasonably diverse set of environments. We’re finding out how well that works. You can amortize the technical investment in the platform and have it really pay off for a wide variety of use cases. At the institute, we’re in a planning phase where we have a list of projects that we’re contemplating doing. We’re getting all our talented people to say things about what they’d like to do. Getting the balance between trying to have robots that do everything and robots that do one thing is a hot topic for us. We’re probably going to pick a couple of activities that span that space and see how it works out.

What were your thoughts on the Tesla Optimus demo?

I thought that they’d gotten a lot more done than I expected, and they still have a long way to go. I thought that their design of the second, nonworking robot was cosmetically very interesting. I’m a Tesla driver. I’ve had a couple of them. I really admire Elon, despite the recent Twitter activity. I think he’s a brilliant guy, and I absolutely wouldn’t count him out.

Why was it important that the company sign a weaponized robotics pledge?

There was a lot of sentiment among the employees that the robots aren’t suitable for weaponizing. There’s so many additional concerns, if a robot were to be weaponized, and we just wanted to say that we shouldn’t be doing it with these. I think there was some unhappiness that it looked like some of the other companies had just kind of flung a weapon on there without maybe necessarily considering all the safety. As much as anything, it’s a friendly fire–type worry.

Robotics companies that are hiring

Boston Dynamics AI Institute (11 roles listed, more on the way)

News

Image Credits: Figure

All right, let’s talk news. First up is Figure. The Sunnyvale-based startup emerged out of stealth this week, six months after we initially reported on its existence. I’m frankly enjoying the reinvigorated debate around general-purpose robots and humanoid form factors reignited by the early Tesla Optimus demo, and the company is aiming to be right in the eye of that storm with the Figure 01.

“The team is ex-Boston Dynamics, Tesla, Apple SPG, IHMC, Cruise [and Alphabet X]. Collectively we align on building a better future for humanity through the intersection of AI and robotics,” Figure founder Brett Adcock tells TechCrunch. “We’ve been fortunate to hire the best in the world at specific skill sets in AI, controls, electrical, integration, software, and mechanical systems. The team believes we’re at a point where we can commercialize robots that have primarily been R&D over the last two decades. This is something a lot of our team has dreamt about doing for a long time.”

Image Credits: Renovate Robotics

Another interesting startup is emerging on the scene. Renovate Robotics is building systems to automate the shingle installation process. Roofing is both dangerous and extremely widespread, making it a prime candidate for these sorts of technologies.

“I’ve seen a lot of hard tech startups go through steep inflection points from the inside during my time at SOSV, and the ones that I was always the most drawn towards were climate focused,” co-founder Dylan Crow told TechCrunch. “All of these companies have a vision that was fundamentally disruptive, and I see the same in where we’re headed at Renovate Robotics. I have huge conviction in my co-founder Andy, as an engineer and a leader who can get us to market. There’s such a fantastic fit between the two of us, and I have a deep gut feel about the jump.”

That’s about all I’ve got in me this week. See you back in the States. Adieu.

Image Credits: Bryce Durbin/TechCrunch

Subscribe to Actuator here.

Barcelona nights by Brian Heater originally published on TechCrunch

English (US) ·

English (US) ·