Clinical trials are the cornerstone of modern medical research, serving the evidence required to prove (or disprove) the safety and efficacy of a new treatment. However, clinical trials are also costly, resource-intensive endeavors that can take many years to reach a stage where a drug or device is deemed ready for a wide-scale rollout.

This is something that Lindus Health is setting out to address, touting itself as a “next-gen contract research organization” (CRO) that makes it faster and easier to run clinical trials. The U.K. startup today announced it has raised $18 million in a Series A round of funding from big-name backers including Spotify investor Creandum, and billionaire entrepreneur Peter Thiel.

Founded out of London in 2021, Lindus was born from observations and frustrations encountered directly by two of the company’s founders. A former venture capitalist at Omers Ventures, Meri Beckwith had direct knowledge of clinical trials through his work with healthtech startups.

“I worked for a bit in venture capital, and I came across companies running their own clinical trials,” Beckwith explained to TechCrunch. “Everyone was universally frustrated with the outcomes. Everyone just constantly complained about how long clinical trials took, how the outcomes were always bad, and there were always mistakes. So as an investor, I thought this is a really interesting area for investment.”

As the global pandemic took hold in 2020, Beckwith also volunteered to participate in several COVID vaccine studies, giving him first-hand insights into the clinical trial process.

“I was just completely shocked to see how unbelievably dysfunctional that was,” Beckwith added. “And this was one of the really big, well-funded phase-three trials. I remember having to download Internet Explorer to even sign up for the clinical trial. The website the CRO had built was on WordPress, and it didn’t have an SSL certificate. And on the clinical trial side, they were just tons of ridiculous errors. So that was a real eye-opener.”

Michael Young, one of Lindus’s two other founders, formerly served as special adviser at Downing Street, assisting the Prime Minister and U.K. Government on myriad issues across the life sciences sphere. While he was involved in a lot of work around health and biotech, Young said that much of the thinking was focused on drug approvals and NHS rollout, rather than “that bit in the middle” — that is, how the clinical trials are actually conducted.

“We just weren’t thinking about that at all,” Young told TechCrunch. “And so it was that experience that made me start digging into what is actually happening with clinical trials. We came to the conclusion that THAT is the bottleneck that’s stopping all the really cool R&D stuff that’s happening from getting to patients.”

Clinical signs

There are numerous upstarts out there seeking to make their mark in the tech-infused clinical trial space, including venture-backed companies such as Science 37, Koneksa, Curebase, and Florence Healthcare to name a few. But Lindus Health says it’s main selling point is that it’s setting out to cover the entire end-to-end process involved in running clinical trials, rather than specific “point” solutions.

“The companies we compete with are the big CROs,” Young said. “This is a massive market, and tech-first CROs have not yet got a foothold.”

For context, a contract research organization (CRO) is a third-party entity that pharmaceutical, biotech, and medical device organizations outsource some of their mission critical work to, such as clinical research. This saves them from having to do all the work themselves internally, allowing them to focus purely on their core product development. The CRO market is significant, pegged as a $77 billion market today with projections that it will grow by 70% within five years. Notable players include IQVIA, which has emerged as a $40 billion juggernaut in the CRO space, doubling its market cap in the past few years.

A typical clinical trial constitutes the initial trial design, including creating a protocol and regulatory submission package; setting up the technology platform to operate the trials; recruiting patients; delivering the program; and collating all the data. Each stage can take years, depending on the size and scope of a clinical trial, which is why Lindus is looking to streamline everything — with the exception of the ethics and regulatory process, which sits under third-party control — and improve on the existing clinical trial software on the market.

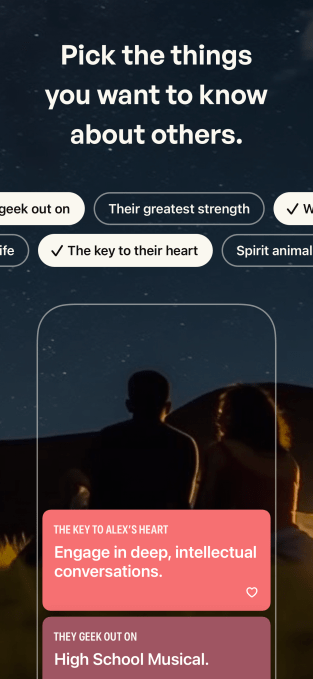

“It’s a cliche that sites (where clinical studies take place) hate the software on the market,” Young said. “We’ve invested thousands of hours speaking to site users to ensure our tool is intuitive and automates the basic tasks that they do. This results in more engaged sites and therefore faster recruitment and better data.”

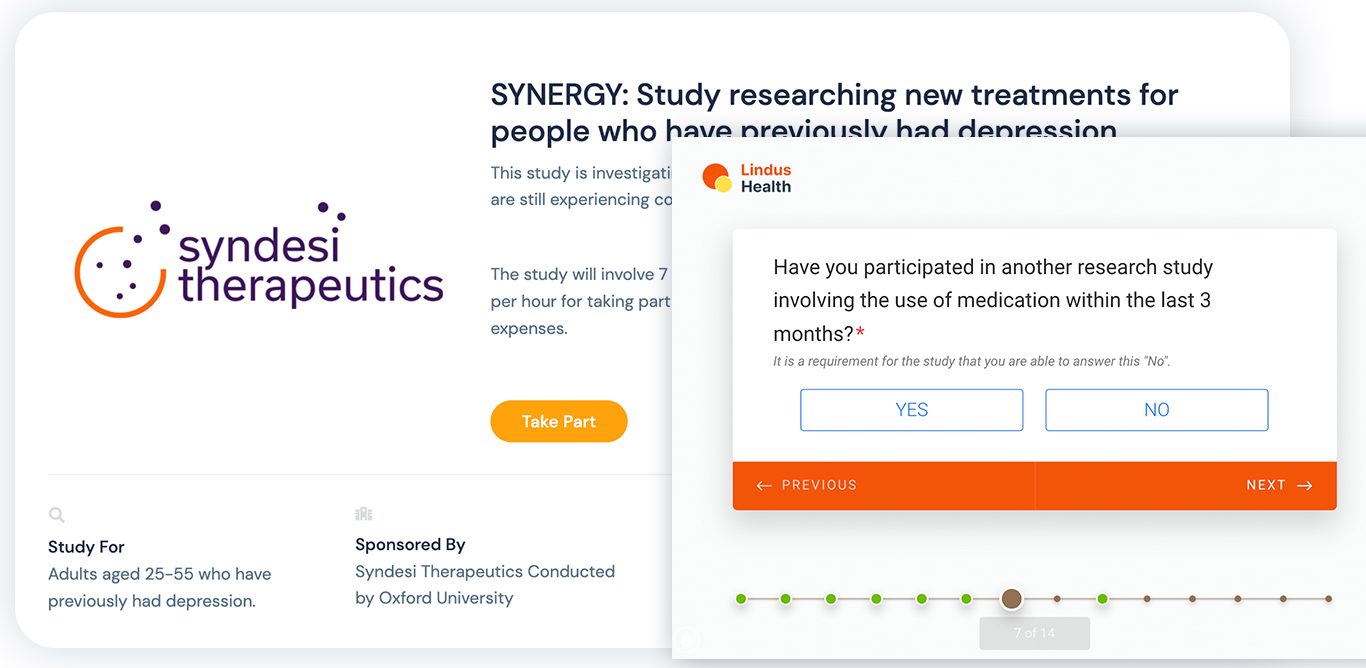

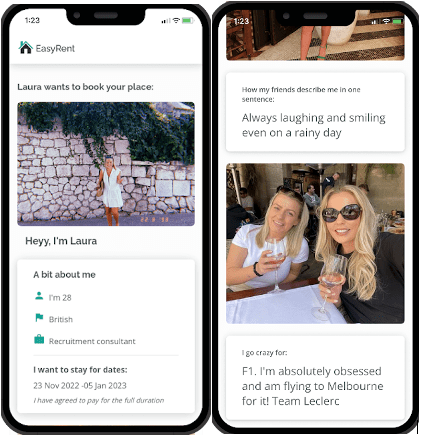

Lindus Health: Recruitment Image Credits: Lindus Health

Part of this streamlining process leans on machine learning (ML), including for the initial protocol writing phase which is typically a very “manual iterative process,” according to Young.

“The result is that, despite the best intentions, there can be contradictions or even seemingly sensible additions which hamstring a trial,” he said. “For example, adding so many exclusion criteria that a trial is almost impossible to recruit for.”

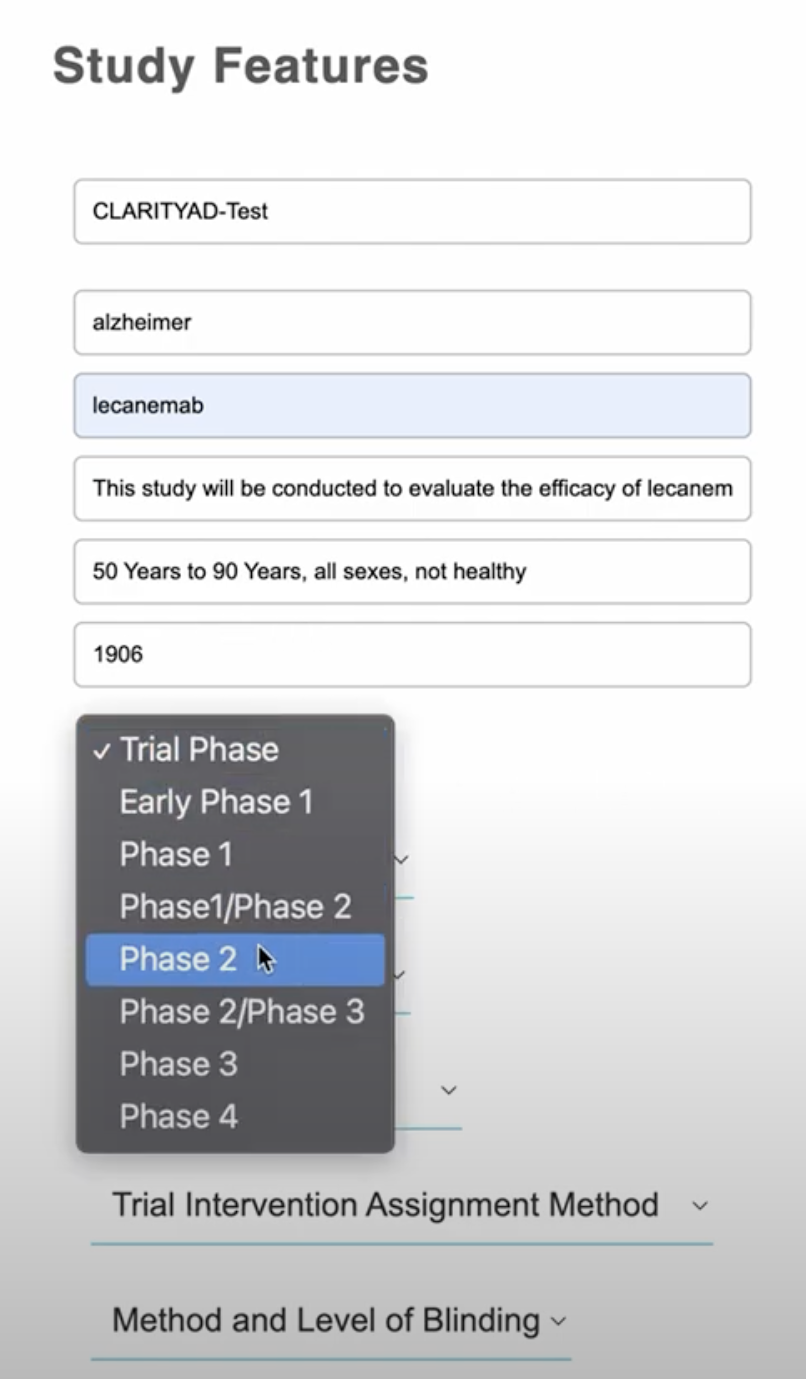

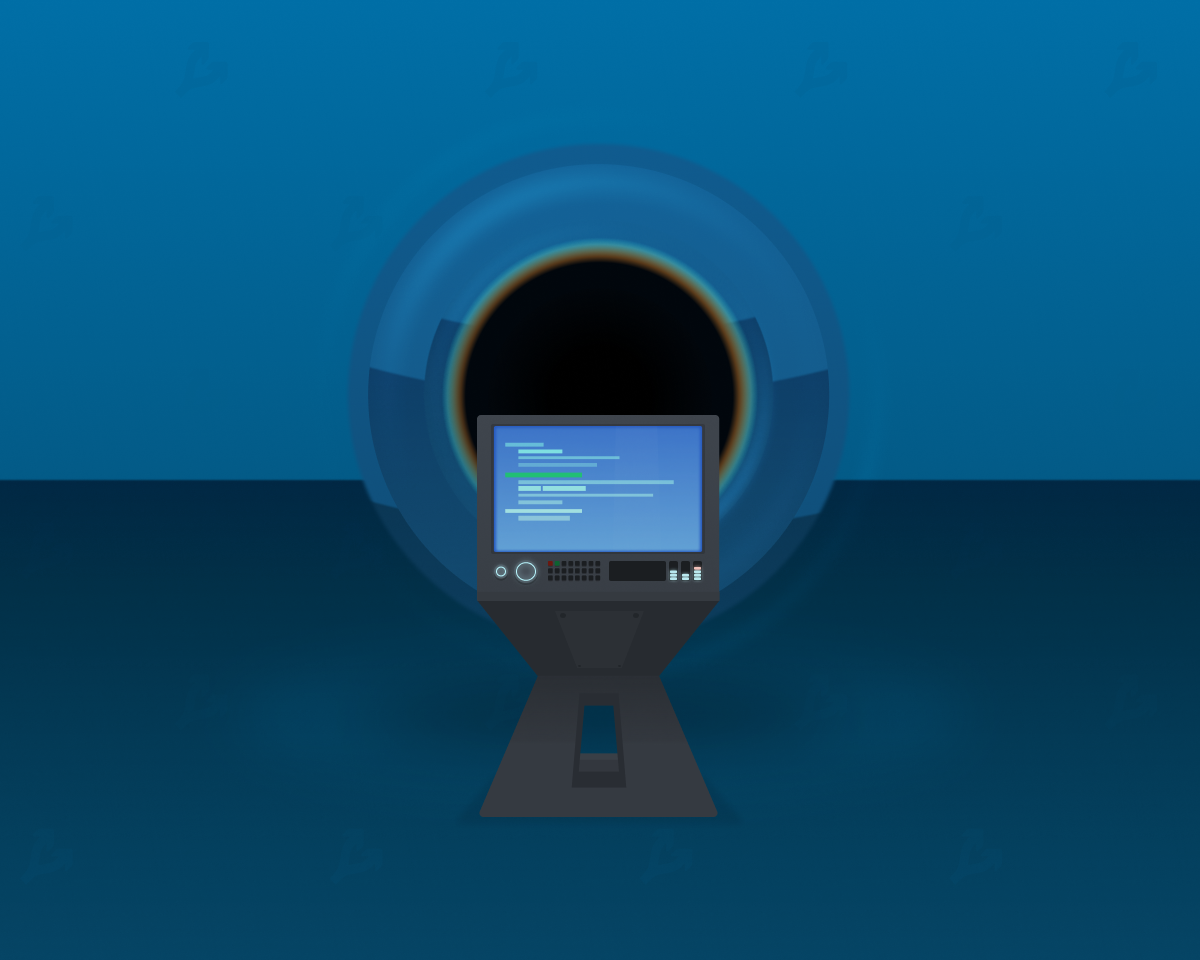

Thus, Lindus has built a “protocol generation” tool, currently at the proof-of-concept stage, trained on its own historical protocols, in addition to protocols gleaned from clinicaltrials.gov, to generate a “first draft protocol based on a small number of inputs,” according to Young. “We can then run this through a separate model that we trained on public data from ScanMedicine that highlights trial risks, and makes suggestions on how to improve the trial.”

Lindus Health AI protocol tool Image Credits: Lindus Health

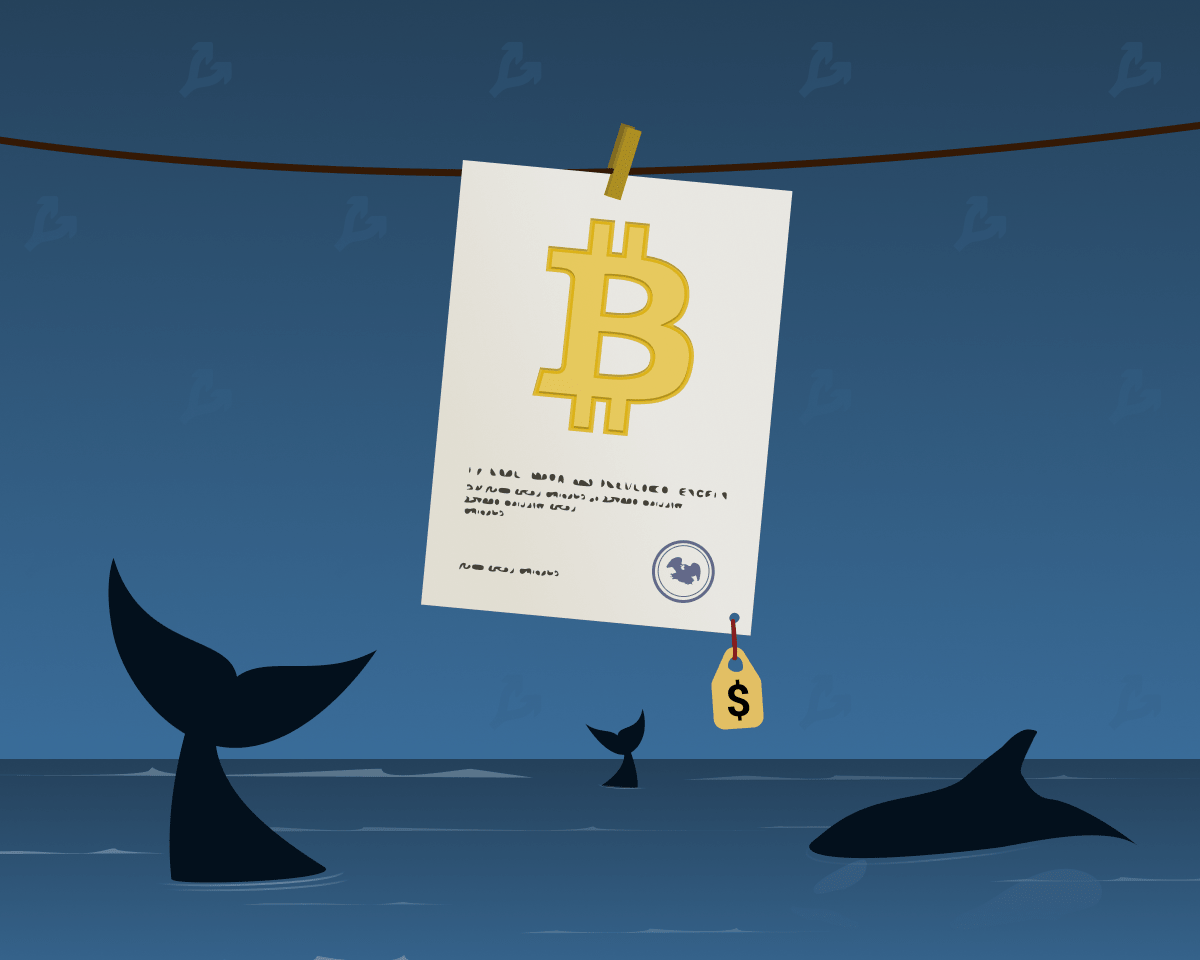

Data capture is a major part of the clinical trial process, something that Lindus supports by allowing trial staff to capture all its data electronically from the get-go, applying AI to monitor and manage the process, while checking for data completeness and accuracy. For this, Young said the company has trained a series of models to analyze data in real-time as its ingested.

Lindus makes all this data available in a centralized dashboard.

“Clinical trials are in essence just a data collection exercise,” Young said. “A standard clinical trial will generate hundreds of thousands to millions of data points. The company running a clinical trial is responsible for ensuring that this data is accurate and that any data that might indicate a risk to patient safety is identified.”

Lindus Health study data dashboard Image Credits: Lindus Health

Human condition

Lindus had hitherto raised around $6 million in funding from some of the very same investors that have joined its Series A round, including Creandum and Peter Thiel. Now, with another $18 million in the bank, the company is well-resourced to ramp up its presence across Europe and North America, where it says it has already delivered more than 80 clinical trials since its inception two years ago.

So far, Lindus has focused on a handful of conditions including depression, diabetes and insomnia. According to Beckwith, there are various factors that dictate which conditions it chooses to support, but it’s mostly about staying focused and not trying to do everything at once.

“On the practical side, our Northstar — and what differentiates us from a lot of companies in this space — is that we’ve always believed strongly that to have an impact and to make a difference, we need to run the entire clinical trial and displace CROs,” Beckwith said. “Then as a startup, we thought, ‘what are the simplest clinical trials we can run, where we can still be in charge of the whole clinical trial?'”

Thus, Lindus has purposely sought to support more common conditions. And while initially it focused on non-drug products which inherently have fewer hurdles to run clinical trials, it has since expanded into drug products and it’s now also looking to extend support to other conditions such as tinnitus, insomnia, menopause, and childhood myopia.

Beckwith added that the pharmaceutical industry has focused its R&D on more niche conditions and rare diseases in recent years, which has meant more common conditions such as type 2 diabetes have been neglected.

“Potentially, the reason that’s happened is because of the clinical trial infrastructure, because putting any patient through clinical trials has such a high cost,” Beckwith said. “Sso economically it’s only made sense for them to run those clinical trials where you can get an approval with few patients, and where that approval leads to a huge dollar-value for one course of treatment. So we think that our strongest competitive advantage is that we’ve just made clinical trials, on the whole, much more scalable.”

Regulation time

Lindus has secured a swathe of backers from different areas of the VC spectrum, including the aforementioned Creandum, Firstminute Capital, Seedcamp, Hambro Perks and Amino Collective. But Peter Thiel is arguably the most notable participant here, given his track record in the healthtech space.

“We got connected to Peter via one of our angel investors, and when we initially spoke, he just went extremely deep on understanding the market for first principles,” Beckwith said. “For example, why the market looks the way it does with the current CROs having a terrible offering, and they have an oligopoly. And Peter’s due diligence, or ‘process’ if you like, was very different from virtually every other investor we spoke to, which is quite refreshing. Essentially, all the questions were framed around, ‘how big could Lindus Health be if we do well.'”

The fact that Thiel, alongside most of Lindus Health’s seed investors, has doubled down on his investment is indicative of how he views the clinical trial status quo. Indeed, as with just about every self-proclaimed libertarian, Thiel has never been one to welcome regulation with open arms. But he’s also a huge proponent of medical advancement, investing in countless biotech companies as part of a longer term plan to, well, live forever. As such, Thiel has been vocal about the hurdles involved in getting new medicines to market. This includes lambasting the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) over how it hinders experimental drugs from getting to market, while he also sparked a furore when he invested in a company that had previously taken its clinical trials offshore and avoided FDA oversight.

However, rules and oversight are usually in place for good reason, especially when it involves drug trials. So any company that comes along proclaiming to up-end an industry renowned for its regulatory oversight might be viewed with a little suspicion. But Young is adamant that they are focused purely on solving technical and process problems, rather than trying to push for change to regulations, something he said would be “a losing battle” as a startup. In truth, lobbying of that sort is something the big pharmaceutical companies themselves are more likely to pursue.

“Clinical trial regulations do evolve, but nothing that we’re doing is in a grey area,” he said. “We definitely think that the regulatory bodies could do more to encourage sponsors to be innovative — but within an existing regulatory framework.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·