As part of our quarterly integrity reporting, we’re sharing a number of updates on our work to protect public debate and people’s ability to connect around the world.

Over the past five years, we’ve shared our findings about threats we detect and remove from our platforms. In today’s threat report, we’re sharing information about three networks we took down for violating our policies against coordinated inauthentic behavior (CIB) and mass reporting (or coordinated abusive reporting) during the last quarter to make it easier for people to see the progress we’re making in one place. We’re also providing an update on our work against influence operations — both covert and overt — in a year since Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. We have shared information about our findings with industry partners, researchers and policymakers.

Here are the key insights from our fourth quarter 2022 Adversarial Threat Report:

- While Russian-origin attempts at covert activity (CIB) related to Russia’s war in Ukraine have sharply increased, overt efforts by Russian state-controlled media have reportedly decreased over the last 12 months on our platform. We saw state-controlled media shifting to other platforms and using new domains to try to escape the additional transparency on (and demotions against) links to their websites. During the same period, covert influence operations have adopted a brute-force, “smash-and-grab” approach of high-volume but very low-quality campaigns across the internet. Notably, the two largest covert operations focused on the war in Ukraine that we disrupted were linked to private actors, including those associated with the sanctioned Russian individual Yevgeny Prigozhin, continuing a number of global trends we’ve called out in our threat reporting. These actors can provide plausible deniability to their customers, but they also have an interest in exaggerating their own effectiveness, engaging in client-facing perception hacking to burnish their credentials with those who might be paying them. It is critical to analyze the impact of these deceptive efforts (or lack of it) based on evidence, not on the actors’ own claims, while continuously strengthening our whole-of-society defenses across the internet.

- In our previous threat reporting, we called out the rise of domestic influence operations, which are particularly concerning when they combine deceptive techniques with the real-world power of a state. The three CIB networks we removed last quarter — in Serbia, Cuba, and Bolivia — continued this trend and were in some way linked to governments or ruling parties in their respective countries. Each targeted domestic populations to praise the government and criticize the opposition.

- We took action against a CIB network in Serbia linked to employees of the Serbian Progressive Party, known as its Internet Team, and state employees from around Serbia. They targeted domestic audiences across many internet services, including Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, in addition to local news media to create a perception of widespread and authentic grassroots support for Serbian President Aleksander Vučić and the Serbian Progressive party.

- We also took down a CIB operation in Cuba that targeted primarily domestic audiences in that country and also the Cuban diaspora abroad. Our investigation linked this network to the Cuban government. The people behind it operated across many internet services, including Facebook, Instagram, Telegram, Twitter, YouTube and Picta, a Cuban social network, in an effort to create the perception of widespread support for the Cuban government.

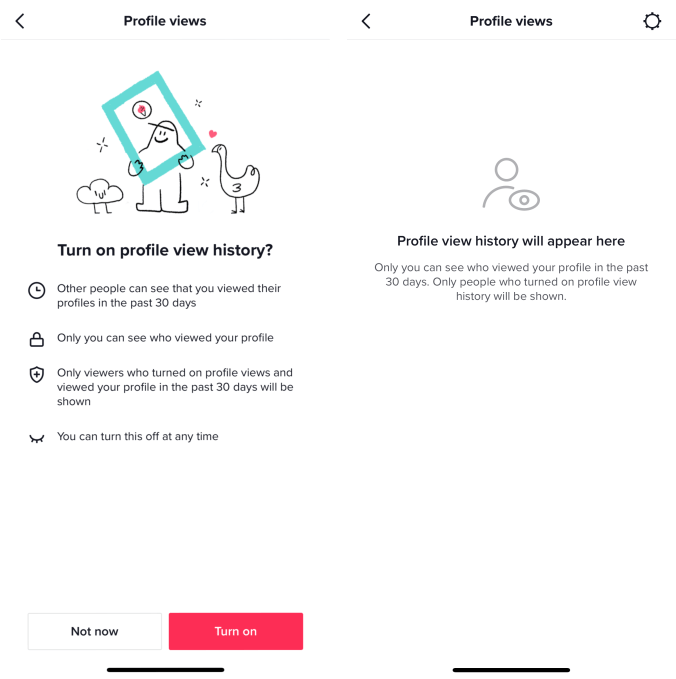

- Finally, we removed a blended operation — coordinated adversarial activities that violated multiple policies at once — in Bolivia linked to the current government and Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS party), including individuals claiming to be part of a group known as “Guerreros Digitales” (“digital warriors”). It engaged in both coordinated inauthentic behavior and mass reporting (or coordinated abusive reporting) in support of the Bolivian government and to criticize and attempt to silence the opposition. This operation ran across many internet services, including Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, TikTok, Spotify, Telegram and websites associated with its own “news media” brands.

We know that adversarial threats will keep evolving in response to our enforcement, and new malicious behaviors will emerge. We will continue to refine our enforcement and share our findings publicly. We are making progress rooting out this abuse, but as we’ve said before — it’s an ongoing effort and we’re committed to continually improving to stay ahead.

See the full Adversarial Threat Report for more information.

The post Meta’s Adversarial Threat Report, Fourth Quarter 2022 appeared first on Meta.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·