A number of native Detroiters have asked me what I think about their city so far. The simple answer is that I don’t feel qualified to offer much insight yet. I’ve been here for roughly three days as I write this, and I haven’t seen all that much of the city. Ask me what I think about the Huntington Place convention center, on the other hand, and I can speak with great authority

I admit that I’m still overly impressed by the fact that, when you walk through the building’s rear entrance, you’re suddenly face-to-face with Canada. It’s something that I may well not have realized were it not for the giant red and white maple leaf flag flying on the Detroit River’s north coast.

I briefly entertained the notion of crossing the border for dinner, for the sole purpose of telling friends that I had dinner in another country, but hailing a rideshare across the bridge wasn’t as straightforward as I’d been led to believe — a fact exacerbated by the fact that it was Victoria Day on Monday (which appeared to visibly impact attendance on the first day of the show).

One thing you’ll find with Detroit is that the people who live there are fiercely loyal to their home — a common characteristic among Rust Belt cities. They cheerlead for the city to all who will listen and defend it with ferocity if you’re foolhardy enough to criticize it. At the same time, however, citizens aren’t blind to — nor do they ignore– decades of struggle. If you know one thing about the city beyond its professional sports teams, it’s likely that its destiny has been shaped by manufacturing probably more so than any other major American city.

Detroit is an industry town, in the purest sense of the term. It’s well positioned in the middle of the country. It has ready access to iron and timber, along with rivers and trains that provide a straight shot to ship heavy machines to and from other major American cities like New York and Chicago. Michigan native Henry Ford incorporated his company in the Detroit suburb Dearborn in 1903. His deeply problematic shadow still looms large over the city, much like Carnegie in Pittsburgh. Ask someone what you should see during your short time in town, and the Henry Ford Museum will invariably make the list. (I opted to spend my limited non-show time at the very good Detroit Institute of Arts instead. Take that, Hank!)

Image Credits: Jose Francisco Arias Fernandez / EyeEm / Getty Images

GM acquired its way into Detroit after being founded 68 miles northwest in Flint in 1908. A year later, the company came within $2 million of adding Ford to its growing list of subsidiaries. (Add that to the list of historical hinge points for the sci-fi book you’re writing.) Walter Chrysler was the last of the big three, founding his namesake corporation out of the ashes of the Maxwell Motor Company in 1925.

If you’re aware of all that, you almost certainly know the other side of the coin: what happens when an industry town’s industry leaves town. While the big three still operate out of the area, the ghost of manufacturing still haunts over the area. First came the decentralization outside of the city proper, and then broader economic troubles and resulting slowed car sales, while increased competition overseas loosened the city/country’s stranglehold on the automotive industry.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

Obviously the full story is far more complex than all of that. Politics and racial inequities played key roles as well. A city so inexorably tied to the automobile was far more motivated to embrace freeways over public transit. These sorts of decisions have a way of increasing both economic and racial disparities. Meanwhile, much of the white population skipped out of the city proper, in favor of the suburbs, which now include some of the wealthiest zip codes in the country. The gulf between the rich and the poor has a way of widening the later you get into capitalism’s progression. I’m reminded of this every time I head home to San Francisco, where people are forced to live out on the streets in front of some of the world’s richest corporations.

Much like my first visits to cities like Pittsburgh and Baltimore, I had certain expectations heading to Detroit for the first time. From my extremely limited experience in both, it seems like Pittsburgh and Detroit, in particular, are on similar paths, but the former has a sizable head start.

One thing many who visit the city will point to are the abandoned buildings. The population decline can’t be ignored. In prosperous post-war 1950, the city claimed 1.85 million residents, making it the fifth largest American city. The 2021 census, however puts the figure at 633,000. Devoid of people, these thriving organisms begin to feel like monuments.

For years, my distant impression of the city has been flavored by stories of revitalization. For one thing, population decreases lead to rent drops, which can, in turn, birth a thriving arts scene. The word “renaissance” has been thrown out many times in recent decades. The fact of life in 2023 is that living in places like New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco can be unattainable on an artist’s income. In recent decades, Detroit has offered a compelling cross section of cheap rent and rich culture — some of the greatest music in the history of the world was produced here. I took a car straight to the Motown house after I landed. There’s something truly magical about a place that gave us Diana Ross, the MC5, Detroit techno, Dirtbombs, The White Stripes and Danny Brown.

At the end of the day, however, a thriving art scene is great at attracting young people but is unfortunately rarely an epicenter for a thriving economy. I’ve also long heard whispers about the return of manufacturing to the city. Certainly Detroit has the infrastructure necessary, and the continued presence of automotive headquarters is key, especially as more companies look to decentralize and localize manufacturing due both to ongoing supply chain concerns and the very real possibility of deepened U.S.–China tensions.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

“I think one of the challenges that we saw exposed during COVID was supply chain issues,” president of the Association for Advancing Automation (A3) and Detroit native Jeff Burnstein told me during a conversation this week. “It’s not easy to do, but a lot of companies would like to bring more manufacturing back to North America. You can’t just rip up your supply chain, of course. . . . But they were able to do it because of automation. One of the limiting factors [for reshoring] is that we don’t have enough people who are skilled.”

There do appear to be some good initiatives in place, and I’m increasingly hearing stories from hardware startups that have been pushing to bring assembly and/or manufacturing closer to home. True, lasting success takes time and a lot of money, along with the concerted efforts of both industry and government. I went to an event last night at Newlab’s shiny new Detroit offices last night. The space and the growing number of startups point to key dollars entering the market.

The campus is located in a fairly remote part of the city, near the Ambassador Bridge, which carries roughly one-quarter of all U.S./Canada merchandise trade each year. The biggest benefit of the area is that there’s plenty of room to grow and — in theory — help foster a thriving startup community. In addition to big tech companies like Google and the native StockX, smaller startups from the area are starting to get national recognition. RoboTire, the robotic tire change firm we’ve written about a few times over the years, served as a kind of poster child at this week’s show. Certainly the company is a great example of leveraging Detroit’s automotive expertise as the foundation of something new and bleeding edge.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

The continued presence of the automotive industry is probably the single largest reason why the Automate show is located here. Burnstein gave me a broad overview.

“Our show had a lot of names,” he explained, offering a quick history of the event. “It started as the Robotics Show in the ’70s. Robots were going to be the next industrial revolution. The show was so big that — I think it was in 1982 — they had to close the escalator to the basement where the show was, because the fire marshal said there were too many people. There were like 30,000 people. It was almost as big as it [is] now. The show followed the fortunes of the industry, which went downhill in the mid-’80s.”

Burnstein lays the blame for the implosion on General Motors’ decision to cut robotics orders. As the major driver of the early industrial robot industry, the decision had a profound impact on the burgeoning category.

“Detroit was the natural home, but then the auto industry stopped buying so much,” he adds. “Our show said we can’t do it every year, and let’s find other places to do it in. We were in Chicago for two decades.” During that time, the event joined forces with the Assembly Show and later MHI’s ProMat. Ultimately both ProMat and Automate grew to a point where each event evolved back into its own separate show, now two of the country’s largest robotics event.

ProMat remains the larger of the two shows. It’s also more focused on a single industry. When I first started discussing the possibility of attending both this year, ProMat was pitched to me as a logistics show and Automate as manufacturing. ProMat started life focused on that space but has increasingly grown into an automation show as robotics have begun to have an outsized influence on the industry. There’s certainly logistics at this event (Locus and Zebra/Fetch were both present, for example — albeit in much smaller booths than at ProMat — but manufacturing (specifically automotive) still feels like its lifeblood. A Fanuc arm holding up a sports car has been the show’s iconic visual for years. Fittingly, you’ll also see a giant Fanuc “Let’s Talk About Automation” ad on the side of an airport parking garage as you arrive — something I’m told is not an Automate-only feature.

Smaller robotics startups were less of a presence at Automate, though they were there in some forms, like the Pittsburgh consortium that brought Shift Robotics’ Moonwalker shoes and drone inventory startup Gather AI. Most of my interactions with founders occurred at after-parties like the one at Newlab and an event put on by robot operating system (ROS) stewards Open Robotics and ROS users PickNik Robotics and Foxglove.

Image Credits: Getty Images / Daryl Balfour

I did, however, line up a couple of chats with some bigger names, including Jim Lawton, the Rethink and Universal Robotics vet who heads up robotics and automation over at Zebra Technologies. If you’ve read about Zebra in this newsletter in the past, it’s because of the company’s 2021 acquisition of Fetch. I’ve likened the deal to Amazon’s acquisition of Kiva from the standpoint of a company buying an existing startup to serve as the foundation of a broader robotics play. In a certain way, it’s actually closer to the Shopify/6 River Systems deal, in the sense that Amazon suddenly left a lot of customers in the lurch after it cut off third-party clients.

Of course, the Shopify situation went pear-shaped as the Canadian e-commerce giant sold off 6 River amid news of far-reaching layoffs. Fetch is third place in the category behind 6 River and Locus, the latter of which is the biggest player by a wide margin. Zebra’s acquisition was clearly an ecosystem play — effectively a bid to start selling robots to customers of its existing services.

Says Lawton:

As the market has matured, customers who are now looking at automation now want solutions to problems. They’re not robotic tinkerers. For a while, it was “These are cool. How fast are they?” Now it’s “How much productivity can I get? How much increased capacity can I get? A lot of that comes from taking robots, these devices, and the ability to control other things in the warehouse, like getting robots up to the mezzanine level, meaning the robot is able to activate the elevator. If I’m going to take a tote off a robot and put it onto a conveyor, I need to activate the conveyer, I need to activate the robot. We have an IoT gateway device that we use to orchestrate all of the other things. What they want is a warehouse workflow optimization tool that happens to involve robots.

We also discussed my favorite topic of recent vintage: interoperability. Lawton again:

I think it’s going to take longer than people think it is. The idea of seamless interoperability is not something we’re going to see a lot of over the next couple of years. It’s going to take some time. I know the markets are different, but there is some precedent on the manufacturing side. Robotic arms have been in manufacturing since the 1960s, and we still don’t have [interoperability]. It’s going to take some time. There are reasons interoperability is more important in the warehouse space. A robotic arm is integrated into a cell. These kinds of robots are a little bit different, so I think you’ll see the pace get a little bit faster.

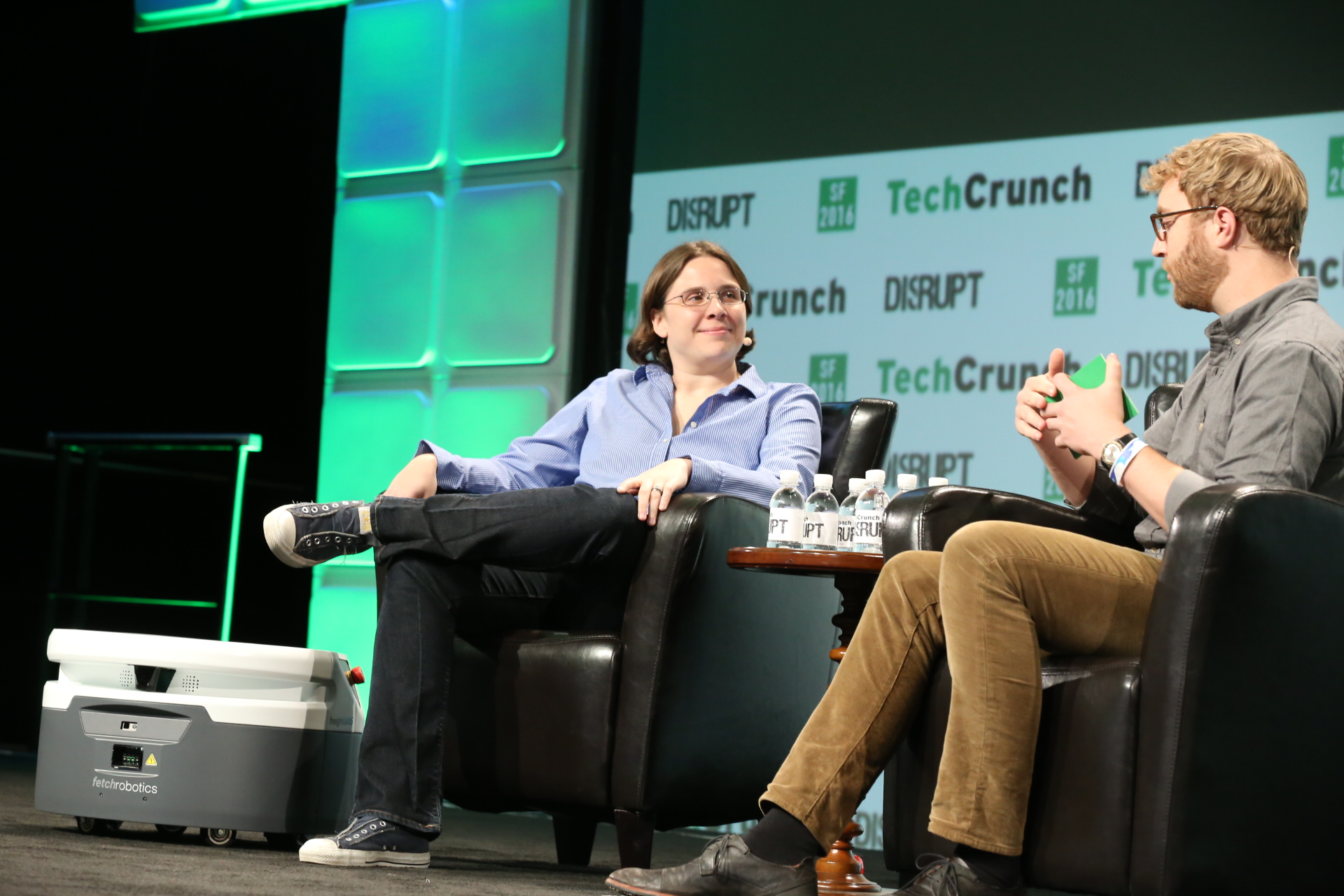

Q&A with Melonee Wise

Image Credits: TechCrunch

Early this week, we were the first with the news that Fetch founder Melonee Wise had left Zebra and joined forces with Agility, where she’ll serve as CTO. The Willow Garage vet knows as much about warehouse robots as just about anyone on the planet. It’s a great hire for Agility, and an interesting challenge for Wise as the company continues to explore commercial applications with Digit.

Wise and I discuss the move and a bunch more:

Let’s start with Agility.

I’m so excited.

I’m sure you’ve known them for a long time.

There was — let’s call it a seminal moment — where [CEO Damion Shelton] and I were at a conference and we ended up on a panel together talking about why robot technology has such a hard time getting out of the university. What is it about robotics technology and crossing the chasm from a cool science project to a full production company that’s shipping robots?

You had already had success with that. It’s scalability, repeatability.

It’s also about what to focus on, when. There’s a lot of perfecting the imperfect that happens where we’re hyperfocused on minutia from a technology perspective that the customer doesn’t care about. If you look at logistics, primarily what the customers care about — if they could just wave a magic wand and get it — they want a teleporter.

To get a product from one place to another.

Yeah. We, as roboticists, are building all these robots to achieve basically that ask. Because they want a teleporter, the customer has a hard time articulating what the need is. We as roboticists — because we don’t get great specifications — we have the tendency to try to really rathole on the things that we know.

You over-engineer.

Yeah. Instead of just throwing it out into the world, letting it fail and then building the thing that customers want.

There’s an extent to which you can fail when starting a company. If Digits went out there, started falling over and lighting on fire, that would be a problem.

Absolutely. But I think there’s a thing that happens in early-stage startups that decides if they’re going to be successful or not. I believe the success point is when you’re at your first customer and it’s not going perfectly.

When you’re still small.

Yeah. It’s that customer that really shapes and helps you define your product — or a set of customers. It’s not going to go well there. No matter how you like to spin it, it doesn’t go well — unless you’re in software and you really have the ability to change things quickly. With robotics hardware, you’re kind of stuck with the thing that you made, and a lot of what you’re doing when you get into your first customer is trying to tweak it or trying to put candy wrapping around it. And then you make a small iteration in software or hardware, and you get closer and closer to what everyone wants to buy. But it’s from that failure that you get a directed purpose for success.

Fetch had that time as a smaller company. Agility’s product is so visually interesting, and it got so much press, that suddenly Ford is interested. That’s a lot of pressure at an early stage.

Yeah, it is. I think that we’re trying as a company as part of scaling to choose customers that we have an opportunity for codevelopment with. It’s not to say that we’re not focusing on the other big customers that are with us; it’s just that we’re diversifying our strategy to make sure that we have these opportunities to learn in a non–high publicity environment.

Also, you find a warehouse so it can be applied to other warehouses. The Ford learnings can be applied to other things.

One of the things that we have been trying to get to is the solution. Fetch struggled with that for a very long time. We started by selling a robot product into the market. But we eventually became a solution.

It makes sense. You started as roboticists, not warehouse experts.

I think that all robotics companies go through that originally. It just matters what end of the spectrum you’re coming from. If you look at the story of Locus, they were product-first people, robotics second.

They were a logistics company that felt like they had to make robots.

Yeah. Their solution came to market a lot more mature, but their robotics hardware came to market less mature. It depends on where you are on the spectrum. Agility, like many robotics companies, comes from a very tech-heavy perspective. There’s still learning about what we have to do, which I’m excited about. That’s why I’m there. I think that we are quickly narrowing in on what the end cases are.

There’s a big, ongoing debate around the necessity of legs.

Wheeled robots struggle with a lot of scenarios. I would say the other better case to talk about with wheeled robots is every time you want to do a task like Digit does, you need a specialized accessory to do it.

In terms of an arm to lift it up?

Yeah. Or in the case of a mobile robot, you wouldn’t solve that with arms. You would most likely make a lifting conveyer piece. The robot would have a little conveyer, it would have a way of grabbing the tote, like a sliding arm, and then shuffle it onto the robot. Then the robot would kick it out onto the conveyer. The problem is that it’s a whole other special accessory that you have to build. At Fetch we had mobile platforms, but most of our business eventually became making specialized accessories for the different vertical applications we cared about. The Digit promise is that we are able to attack more vertical use cases with less hardware modification. We have a much more — let’s not say general purpose — but multipurpose [way]. It’s a lot easier to envision a single piece of hardware being used for multiple purposes and a facility for these types of activities.

There are certain things that wheeled robots just can’t do. We have a hard time in general with going over bumps or ramps, largely because it causes problems with safety and localization mapping. One of the more hilarious things about going up a ramp with a mobile robot is as you approach the ramp, it looks more and more like a wall.

Wile E. Coyote syndrome.

There’s some nuance there. That is not to say that mobile robots aren’t a good solution for a lot of use cases. It’s just that when you’re starting to look at this vision of end to end automation with these different agents, there’s a class of things that certain agents are good at. And there’s a class of things that other agents are.

Is it too difficult — or impossible — to put the arm solution on an AMR?

As someone who’s built AMRs with arms — Fetch had a research project that had an arm; we sold about 100 of them over five or six years to research institutes — I think it’s hard to do bi-manual manipulation on a mobile manipulator because of the hardware constraints like putting [on] two robot arms, like Kuka is.

There’s a difference between a Kuka arm and the simpler arms on Digit.

I would say that still — even to implement the framework that Digit has on a mobile platform, there are some limitations that you would run into. There are some advantages to having a base with legs. One of the things you can’t do with mobile platforms is you can’t get below the top of the platform. Digit has a lot of capability in terms of crouching and also reaching that are challenges with mobile platforms from a stability perspective, from a footprint and space perspective.

Image Credits: Agility Robotics

Is the [Digit] arm diverse enough now to continue to diversify the tasks it can perform?

We’re doing some tweaks to the arm, so you’ll see a bit more complexity come into the arm to deal with some of the challenges with the payload moving inside the tote.

In terms of throwing the robot off-balance?

In terms of being able to keep the tote level and things like that. I think we are on a path that makes sense for the right level of complexity to solve the right level of complexity problem. I don’t think we as Agility have ever said we’re making complex, dexterous mobile manipulators with five-finger hands. I’m not convinced that’s the right way to approach the problem in general.

What does the path look like for Agility, going forward? Does everything continue to revolve around Digit?

Let me preface this by saying I’ve been with Agility for five whole days. I would say that I think there’s going to be a large focus on Digit for the foreseeable future, I think that we are going to have to expand our automation story. Fetch did the same thing. We started with a robot, and then we had a robot that interacted with conveyers and these types of devices. Digit’s equivalent is we have to interact with conveyers and put walls.

What’s the solution for Digit? Accessories or a pure software play?

There will be accessories; there will be a software platform that allows us to connect. We’re going to be expanding our fleet management platform and things like that. And also expanding to connect to standard automation tools and partnering to connect with companies that are well known in the automation industry.

Is there a lot of overengineering happening on the humanoid side of the robotics world?

It’s hard to say, because it’s hard to say what the use case is. It would depend on what you’re trying. Take robotic picking? How many picking cells have you seen that have five-fingered hands?

They’re all suction cups now.

Suction cups and soft gripping clients. We first need to ask ourselves what is the use case? If you look at the manufacturing and logistics domains, there’s enough prior art that shows five-fingered hands are not necessary.

The hand is just one example, but it does get to the broader point about potentially overengineering.

I’m hesitant to say “overengineering.” I would say it’s just poorly targeted product design.

We talked a bit about your decision to join Agility, but why was this the right time to leave Zebra?

To be more clear, I went from being the CEO to a CTO for the Robotics Business unit. We transitioned into Zebra. It was a big change for me, but although the work was interesting, it was not as fulfilling as I wanted it to be for me, personally. After about 18 months of being at Zebra, I decided it was the right time for me to leave. I decided to take some time off. Running a company for seven years — and having a plethora of different life events that happened during that period — I needed a break. I decided to take six months off. I think it was a good thing for me, personally. We don’t talk enough about founder health and things like that.

Being a CTO is obviously still a hard job, but it almost sounds like a relief to be able to just focus on the tech stuff.

I’m not gonna lie. Moving to Agility is going to be — it’s weird to say this — relaxing to not have some of the burden of being CEO. I’m really excited about that.

You were doing a lot of things you didn’t study for.

Yeah, and also there’s a lot of weird pressure that falls on you as a CEO. For me, some of those pressures were a little bit more extreme, being a woman. And fundraising is not my favorite activity. I, personally, will find it very relaxing to be the CTO of Agility, because I won’t be the CEO. I think Damion is a great CEO and I think he’s doing work that is thankless.

How are you and [former CTO turned chief robotics officer] Jonathan Hurst going to work together?

The way that I see it is Jonathan is very focused on building the innovation pipeline for the robotics hardware. He created Cassie, he created all of the iterations before that. He is going to be building the future technology that Digit will one day rely on. My focus is going to be more product centric.

More news

Image Credits: Apptronik (opens in a new window)

On the humanoid robot front (where we seem to spend a lot of our time these days), I sat down with Apptronik CEO Jeff Cardenas in the otherwise empty Huntington Place cafeteria to discuss the Austin company’s plans to unveil exactly that this summer. The company didn’t have a who presence on the floor, but Cardenas had a slideshow on his MacBook that he was sharing with a select few, including myself. It started with the company’s varied history.

“[The] exoskeleton was liquid cooled,” he told me. “We learned a lot doing that. The complexity of the system was too high. It was heavy. We remotized all of the actuators. And then we started to realize what was the simplest version of a humanoid robot: a mobile manipulator. We started getting approached by a lot folks in logistics, who didn’t want to pay for manufacturing arms. They were too precise for what they need. What they wanted was an affordable robotic logistics arm.”

I can’t share images of the system with you at this point, but I can describe what I saw. Quoting myself:

Cardenas shows me images — both renders and photos — of Apollo, the system it plans to debut this summer. I can’t share them here, but I can tell you that the design bucks the kind of convergent evolution I’ve described, which found Tesla, Figure and OpenAI-backed 1X showing renders with a shared designed language. Apollo looks — in a word — friendlier than any of these systems and the NASA Valkyrie robot that came before it.

It shares a lot more design qualities with Astra. In fact, I might even go so far as describing it as a cartoony aesthetic, with a head shaped like an old-school iMac, and a combination of button eyes and display that comprise the face. While it’s true that most people won’t interact with these systems, which are designed to operate in places like warehouses and factory floors, it’s not necessary to embrace ominousness for the sake of looking cool.

Image Credits: Figure

Apptronik will be exploring a Series A this year, once the robot is revealed and — hopefully — drives investor interest. Meanwhile, one of the company’s chief competitors, Figure, just announced its own $70 million Series A, shortly after its own humanoid robot took its first steps days before the company’s first anniversary.

“We’re focused on investing in companies that are pioneers in AI technology, and we believe that autonomous humanoid robots have the potential to revolutionize the labor economy,” investor Parkway Venture Capital’s Jesse Coors-Blankenship said in a prepared statement. “We are impressed by the rapid progress that Brett and the team of industry experts at Figure have made in the last year and are thrilled to be a financial partner to provide resources to accelerate the commercialization of Figure 01.”

Image Credits: Brian Heater

I’m finishing up this week’s Actuator from Gate A17 at the Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport in Romulus, MI (track nine from Sufjan Stevens’ seminal 2003 album, Michigan). I capped off my first Automate with dinner at Huntington Place’s Grand Riverview Ballroom for the bi-annual Joseph F. Engelberger Robotics Award (though it seems the show will soon be going yearly, along with Automate itself).

The award’s namesake, Joseph F. Engelberger, is credited with co-developing Unimate, the first industrial robot, alongside George Devol in the 50s. The arm would eventually be installed in a General Motors assembly line, making it an innovation decades ahead of its time. The award is regarded as one of the industry’s most prestigious (A3 likes to call it the “Nobel Prize of Robotics”).

Jeff Burnstein fittingly received one of the awards, alongside longtime Universal Robotics employee, Roberta Nelson Shea. Burnstein’s story was a nice one — that of a Detroit native who has had a front row for the dizzying highs and lows of his city and industry alike. Shout out to a fellow English major (though they called it “Literature” where I went to school) who somehow ended up involved in the robot space. Perhaps there are more of us. Let’s start a club.

To hear her tell it, Nelson Shea’s journey was also unexpected. UR’s Global Technical Compliance Officer is best known for her tireless efforts to promote robot safety. Between cobots, HRI and countless hardware and software innovations, the subject is now central to the way with think about industrial robots. The standards Shea helped create are a big piece of that.

“This award is a testament to the great contribution Roberta has made to the robotics industry,” says UR President Kim Povlsen. “Her dedication to safety has helped create the standards for the interaction between people and robots. This has been an important contribution to the collaborative relationship we see today between humans and robots across hundreds of thousands of workplaces.”

And Nelson Shea in her own words, “The Engelberger Robotics Award for Application in Safety is a tremendous honor to me and to all those who have embraced and contributed to robotic safety. I remember meeting Joe Engelberger over 40 years ago and never imagined receiving this award. I view the award to be honoring the industry’s progress in optimizing safety and productivity. The journey has been amazing!”

Image Credits: Bryce Durbin / TechCrunch

Rev up your engines and subscribe to Actuator.

Motor City mechatronics by Brian Heater originally published on TechCrunch

English (US) ·

English (US) ·