We often think of NASA as an agency that looks outward into space, but it’s the agency’s position in space that makes it such a powerful tool for observing the Earth itself. Today NASA announced the results of two space-based studies observing climate change across the planet.

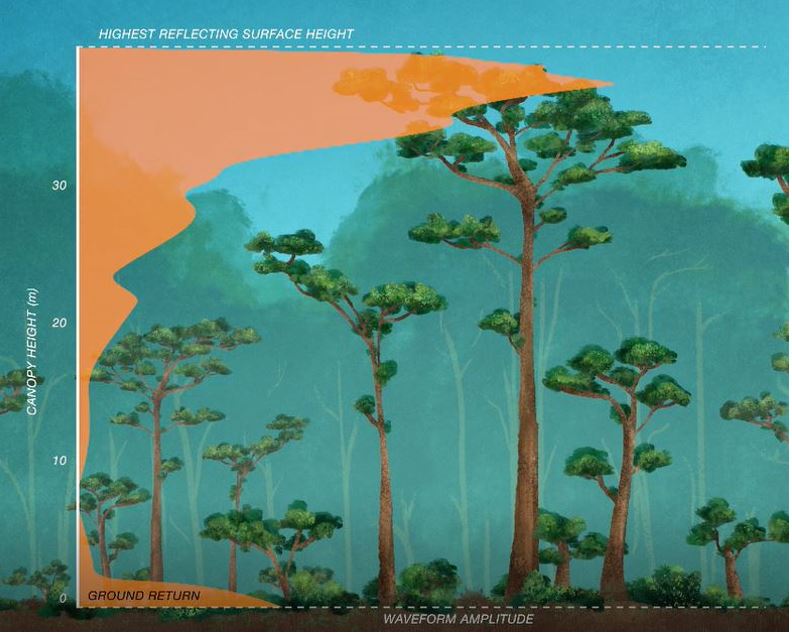

The first is a data set from the Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) mission, a high-resolution lidar instrument aboard the International Space Station (ISS) that has estimated the total amount of above-ground forest biomass and its carbon storage capacity. That information can now be used by researchers studying the role of forests in mitigating climate change.

Over the past three years, GEDI has taken billions of laser measurements of vegetation around the globe. That data has been combined with airborne and ground-based lidar surveys to create detailed 3D biomass maps that indicate the total amount of vegetation in a one-square-kilometer area. With those maps, researchers will be able to better estimate the amount of carbon that is stored in forests.

“Resolving the structure of different forest and woodland ecosystems with much more certainty will benefit not only carbon stock estimation, but also our understanding of their ecological condition and the impact of different land management practices,” John Armston, GEDI’s lead for validation and calibration and an associate research professor at the University of Maryland, said in a press release.

Image Credits: NASA

The second item is a joint project between NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, which used satellite data to develop a method of monitoring underground water loss, a serious matter for the agriculture industry. Researchers observed California’s Tulare Basin with the U.S.-European Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) and GRACE Follow-On satellites and a European Space Agency (ESA) Sentinel-1 satellite.

The groundwater in the Tulare Basin is pumped to irrigate the state’s Central Valley, a major agricultural center in the United States, and its supply is dwindling. The satellite data provided the team the context to develop a model that monitors the rate and type of water loss underground.

“The method sorts out how much underground water loss comes from aquifers confined in clay, which can be drained so dry that they will not recover, and how much comes from soil that’s not confined in an aquifer, which can be replenished by a few years of normal rains,” wrote NASA in a press release.

Even as NASA looks to return to the moon, the agency has reiterated its commitment to Earth science missions. NASA Deputy Administrator Pam Melroy addressed the agency’s prioritization of climate change research at the 37th annual Space Symposium in Colorado Springs, Colorado, this week.

“This year with our international partners, we initiate the Earth System Observatory, a series of Earth-observing satellites that will measure key parameters to improve the world’s understanding of climate change,” she said at the conference. “As we have measured Earth in the past, we’ve discovered that the most important thing to quantify is not just water or weather or soil moisture or any individual thing, but actually to study Earth as a system. And so NASA’s work here in the Earth System Observatory is critical for the entire planet.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·