Two weeks ago, the password manager giant LastPass disclosed its systems were compromised for a second time this year.

Back in August, LastPass found that an employee’s work account was compromised to gain unauthorized access to the company’s development environment, which stores some of LastPass’ source code. LastPass CEO Karim Toubba said the hacker’s activity was limited and contained, and told customers that there was no action they needed to take.

Fast forward to the end of November, and LastPass confirmed a second compromise that it said was related to its first. This time around, LastPass wasn’t as lucky. The intruder had gained access to customer information.

In a brief blog post, Toubba said information obtained in the August incident was used to access a third-party cloud storage service that LastPass uses to store customer data, as well as customer data for its parent company GoTo, which also owns LogMeIn and GoToMyPC.

But since then, we’ve heard nothing new from LastPass or GoTo, whose CEO Paddy Srinivasan posted an even vaguer statement saying only that it was investigating the incident, but neglected to specify if its customers were also affected.

GoTo spokesperson Nikolett Bacso Albaum declined to comment.

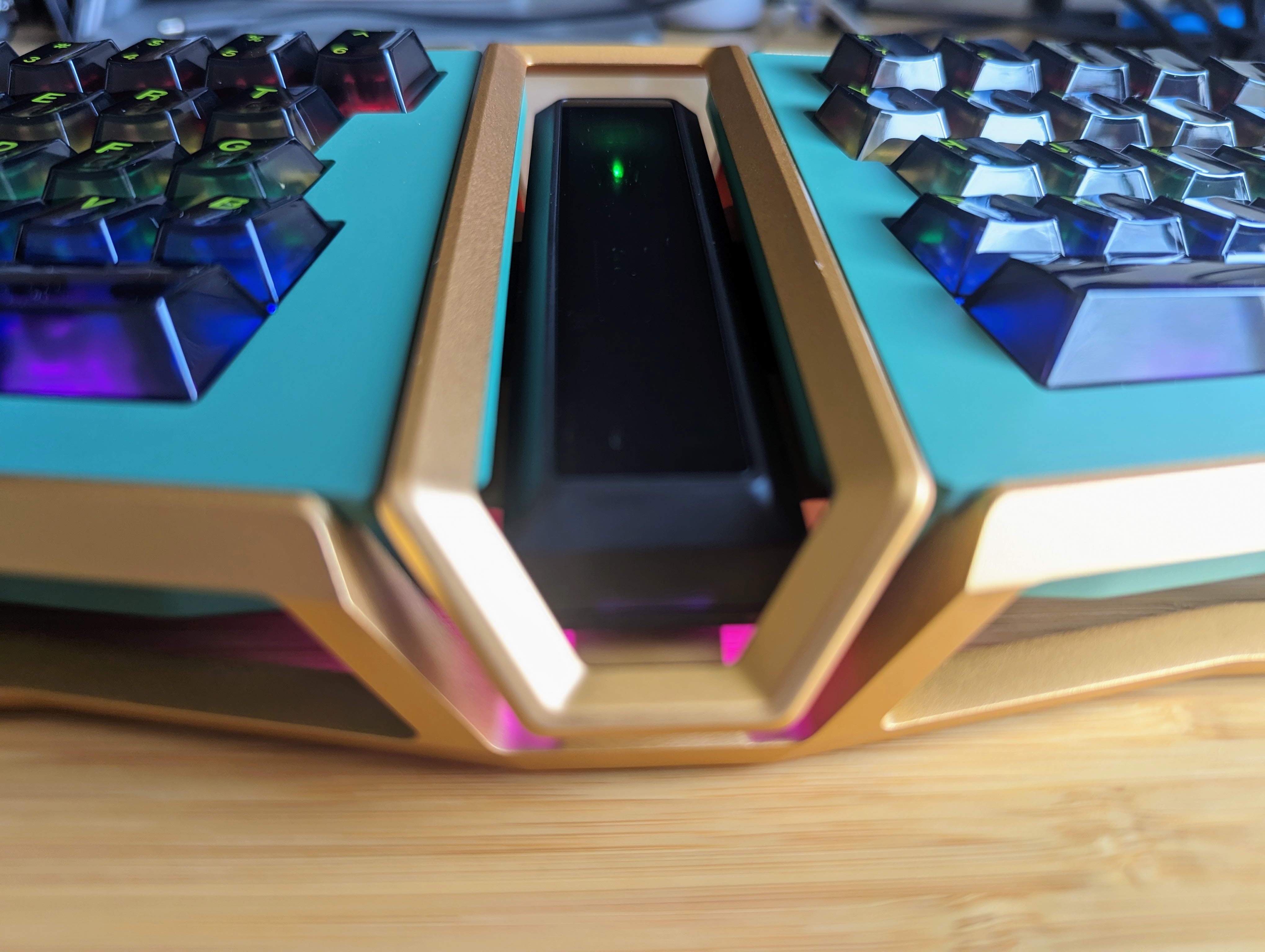

Over the years, TechCrunch has reported on countless data breaches and what to look for when companies disclose security incidents. With that, TechCrunch has marked up and annotated LastPass’ data breach notice  with our analysis of what it means and what LastPass has left out — just as we did with Samsung’s still-yet-unresolved breach earlier this year.

with our analysis of what it means and what LastPass has left out — just as we did with Samsung’s still-yet-unresolved breach earlier this year.

What LastPass said in its data breach notice

LastPass and GoTo share their cloud storage

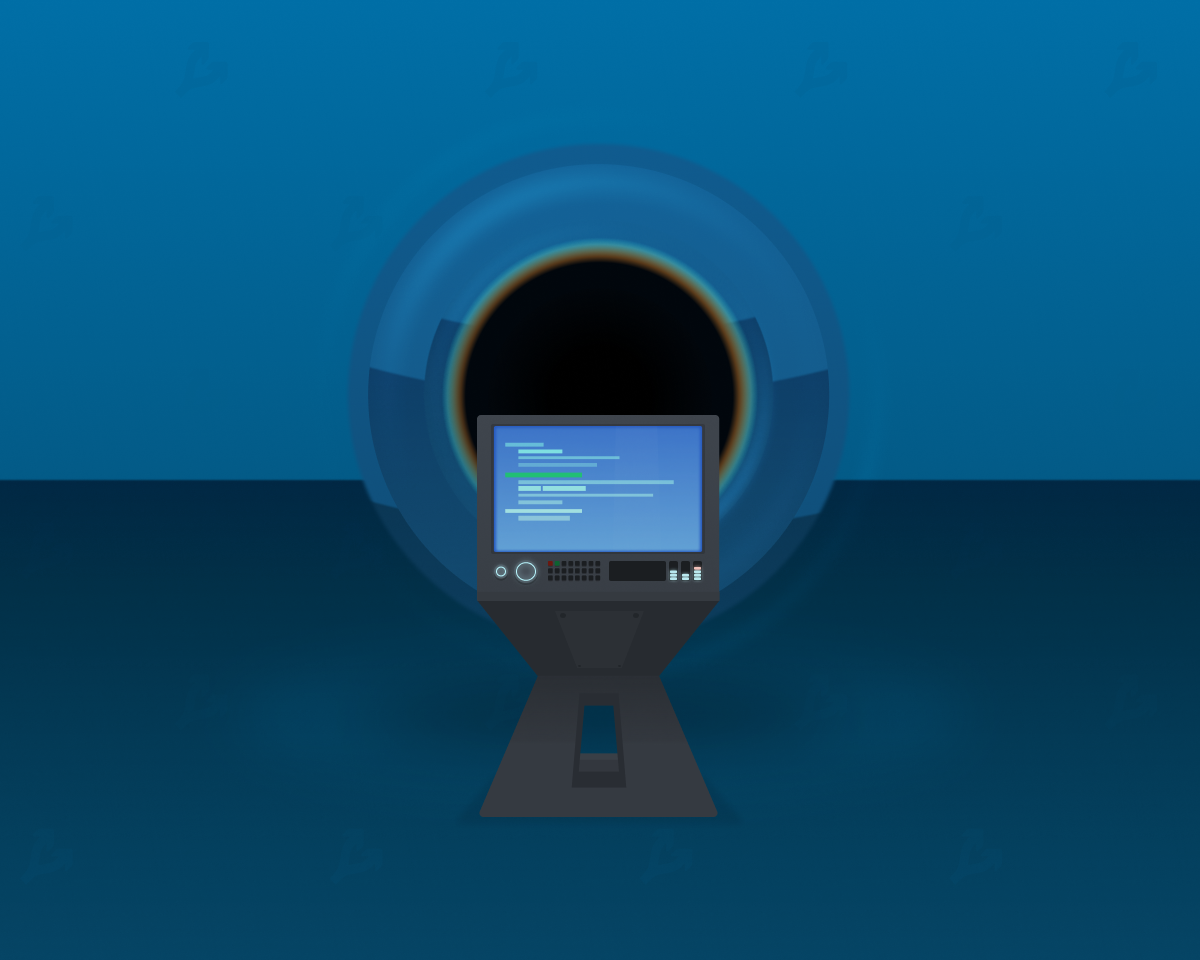

A key part of why both LastPass and GoTo are notifying their respective customers is because the two companies share the same cloud storage  .

.

Neither company named the third-party cloud storage service but it’s likely to be Amazon Web Services, the cloud computing arm of Amazon, given that an Amazon blog post from 2020 described how GoTo, known as LogMeIn at the time, migrated over a billion records from Oracle’s cloud to AWS.

It’s not uncommon for companies to store their data — even from different products — on the same cloud storage service. That’s why it’s important to ensure proper access controls and to segment customer data, so that if a set of access keys or credentials are stolen, they cannot be used to access a company’s entire trove of customer data.

If the cloud storage account shared by both LastPass and GoTo was compromised, it may well be that the unauthorized party obtained keys that allowed broad, if not unfettered access to the company’s cloud data, encrypted or otherwise.

LastPass doesn’t yet know what was accessed, or if data was taken

In its blog post, LastPass said it was “working diligently” to understand what specific information  was accessed by the unauthorized party. In other words, at the time of its blog post, LastPass doesn’t yet know what customer data was accessed, or if data was exfiltrated from its cloud storage.

was accessed by the unauthorized party. In other words, at the time of its blog post, LastPass doesn’t yet know what customer data was accessed, or if data was exfiltrated from its cloud storage.

It’s a tough position for a company to be in. Some move to announce security incidents quickly, especially in jurisdictions that obligate prompt public disclosures, even if the company has little or nothing yet to share about what has actually happened.

LastPass will be in a far better position to investigate if it has logs it can comb through, which can help incident responders learn what data was accessed and if anything was exfiltrated. It’s a question that we ask companies a lot and LastPass is no different. When companies say that they have “no evidence” of access or compromise, it may be that it lacks the technical means, such as logging, to know what was going on.

A malicious actor is probably behind the breach

The wording of LastPass’ blog post in August left open the possibility that the “unauthorized party” may not have been acting in bad faith.

It is both possible to gain unauthorized access to a system (and break the law in the process), and still act in good faith if the end goal is to report the issue to the company and get it fixed. It might not let you off a hacking charge if the company (or the government) isn’t happy with the intrusion. But common sense often prevails when it’s clear that a good-faith hacker or security researcher is working to fix a security issue, not cause one.

At this point it’s fairly safe to assume that the unauthorized party  behind the breach is a malicious actor at work, even if the motive of the hacker — or hackers — is not yet known.

behind the breach is a malicious actor at work, even if the motive of the hacker — or hackers — is not yet known.

LastPass’ blog post says that the unauthorized party used information obtained  during in the August breach to compromise LastPass a second time. LastPass does not say what this information is. It could mean access keys or credentials that were obtained by the unauthorized party during their raid on LastPass’ development environment in August, but which LasPass never revoked.

during in the August breach to compromise LastPass a second time. LastPass does not say what this information is. It could mean access keys or credentials that were obtained by the unauthorized party during their raid on LastPass’ development environment in August, but which LasPass never revoked.

What LastPass didn’t say in its data breach

We don’t know when the breach actually happened

LastPass did not say when the second breach happened, only that it was “recently detected”  , which refers to the company’s discovery of the breach and not necessarily the intrusion itself.

, which refers to the company’s discovery of the breach and not necessarily the intrusion itself.

There is no reason why LastPass, or any company, would withhold the date of intrusion if it knew when it was. If it was caught fast enough, you would expect it to be mentioned as a point of pride.

But companies will instead sometimes use vague terms like “recently” (or “enhanced”), which don’t really mean anything without necessary context. It could be that LastPass didn’t discover its second breach until long after the intruder gained access.

LastPass won’t say what kind of customer information could have been at risk

An obvious question is what customer information is LastPass and GoTo storing in their shared cloud storage? LastPass only says that “certain elements” of customer data  were accessed. That could be as broad as the personal information that customers gave LastPass when they registered, such as their name and email address, all the way through to sensitive financial or billing information and customers’ encrypted password vaults.

were accessed. That could be as broad as the personal information that customers gave LastPass when they registered, such as their name and email address, all the way through to sensitive financial or billing information and customers’ encrypted password vaults.

LastPass is adamant that customers’ passwords are safe due to how the company designed its zero knowledge architecture. Zero knowledge is a security principle that allows companies to store their customers’ encrypted data so that only the customer can access it. In this case, LastPass stores each customer’s password vault in its cloud storage, but only the customer has the master password to unlock the data, not even LastPass.

The wording of LastPass’ blog post is ambiguous as to whether customers’ encrypted password vaults are stored in the same shared cloud storage that was compromised. LastPass only says that customer passwords “remain safely encrypted”  which can still be true, even if the unauthorized party accessed or exfiltrated encrypted customer vaults, since the customer’s master password is still needed to unlock their passwords.

which can still be true, even if the unauthorized party accessed or exfiltrated encrypted customer vaults, since the customer’s master password is still needed to unlock their passwords.

If it comes to be that customers’ encrypted password vaults were exposed or subsequently exfiltrated, that would remove a significant obstacle in the way of accessing a person’s passwords, since all they would need is a victim’s master password. An exposed or compromised password vault is only as strong as the encryption used to scramble it.

LastPass hasn’t said how many customers are affected

If the intruder accessed a shared cloud storage account storing customer information, it’s reasonable to assume that they had significant, if not unrestricted access to whatever customer data was stored.

A best case scenario is that LastPass segmented or compartmentalized customer information to prevent a scenario like a catastrophic data theft.

LastPass says that its development environment, initially compromised in August, does not store customer data. LastPass also says its production environment — a term for servers that are actively in use for handling and processing user information — is physically separated from its development environment. By that logic, it appears that the intruder may have gained access to LastPass’ cloud production environment, despite LastPass saying in its initial August post-mortem that there was “no evidence” of unauthorized access to its production environment. Again, it’s why we ask about logs.

Assuming the worst, LastPass has about 33 million customers. GoTo has 66 million customers as of its most recent earnings in June.

Why did GoTo hide its data breach notice?

If you thought LastPass’ blog post was light on details, the statement from its parent company GoTo was even lighter. What was more curious is why if you searched for GoTo’s statement, you wouldn’t initially find it. That’s because GoTo used “noindex” code on the blog post to tell search engine crawlers, like Google, to skip it and not catalog the page as part of its search results, ensuring that nobody could find it unless you knew its specific web address.

Lydia Tsui, a director at crisis communications firm Brunswick Group, which represents GoTo, told TechCrunch that GoTo had removed the “noindex” code blocking the data breach notice from search engines, but declined to say for what reason the post was blocked to begin with.

Some mysteries we may never solve.

Parsing LastPass’ data breach notice by Zack Whittaker originally published on TechCrunch

English (US) ·

English (US) ·