The web is a living thing — ever-evolving, ever-changing. This goes beyond just the content on websites; whole domains can expire and be taken over, allowing corners of the internet to become a little like your hometown: Wait, wasn’t there a Dairy Queen here?

For example, if TechCrunch forgets to pay its domain registrar, TechCrunch.com would eventually expire (on June 10, to be exact). At that point, some enterprising human could snap up the domain and do nefarious things with it. Now, if TechCrunch.com was suddenly red instead of green and sold penis enhancement pills instead of dicking around with great news and awful puns in equal measure, you’d probably figure out that something is up. But black-hat SEO tricksters are subtler than that.

When they seize a domain, they’ll often point the web domain to a new IP address, resurrect the site, and restore it to as close as it can to the original, and leave it for a while. When the IP address changes, SEO experts claim that Google temporarily “punishes” the domain by dropping it in the rankings.

This is called “sandboxing,” or “the sandbox period,” and during this time, Google puts the domain on notice. Once Google determines — sometimes erroneously — that the IP address change underneath the domain was just part of a move from one web host to another, the theory is that the domain will start climbing in the rankings again. That’s when the new owner of the domain can start their sneaky business: Updating links to send traffic to new places for example, or keeping the traffic as it is and adding affiliate links to make money off its visitors. At the far end of the scamming spectrum, they can use the good name and reputation of the original business to scam or trick users.

Since the invention of PageRank in 1996, Google has been relying in part on the transferability of trust to determine what makes a good website. A site that is linked to by a lot of high-trust websites can, generally, be trusted. Links from that page can, in turn, be used as a measure of trust as well. Massively simplified, it boils down to this: The more links from high-quality sites a page has, the more it is trusted, and the better it ranks in the search engines.

While bad actors can take advantage of this fact, it’s also just something that happens on the internet — sites move from one host to another all the time for perfectly legitimate reasons. As Google’s Search Liaison, Danny Sullivan, pointed out when I talked to him about expired domains last week, TechCrunch itself has had a few changes of owners over the years, from AOL, to Oath, to Verizon Media, to Yahoo, which itself was bought by Apollo Global Management last year. Every time that that happens, there’s a chance that the new corporate overlords want to move stuff to new servers or new technology, which means that the IP addresses will change.

“If you were to purchase a site — even TechCrunch; I think it was AOL who bought you guys — the domain registry would have changed, but the site itself didn’t change the nature of what it was doing, the content that it was presenting, or the way that it was operating. [Google] can understand if domain names change ownership,” Sullivan said, pointing out that it’s also possible for the content to change without the underlying architecture or network topography shifting. “The site could rebrand, but just because it rebranded itself doesn’t mean that the basic functions of what it was doing had changed.”

The buying and selling of expired domains

You don’t have to look far to find places to buy expired domains. Serp.Domains, Odys, Spamzilla, and Juice Market are some of the most active in the business. (As a side note, I stuck a rel="nofollow" on all three of those links in the HTML of this article. They ain’t getting TechCrunch’s sweet, sweet link juice on my watch; as Google notes in its developer documentation; “Use the nofollow value when … you’d rather Google not associate your site with … the linked page.”)

A screenshot from Serp Domains, which lists around a hundred sites for sale, noting that “aged expired domains are not affected by the sandbox effect.” The company lists prices from $350 to $5,500, with original registration years ranging from 1998 to 2018.

“Get expired domains that have naturally gained (almost impossible to get) authoritative backlinks since they were actual businesses,” Odys advertises on its site, adding that they “are aged and out of the sandbox period by a mile, [and] already have organic, referral & direct, type-in traffic.”

These domains are listed for sale for anything from a few hundred bucks to thousands of dollars. Seeing the sites disappear from the “for sale” list and then pop up on the internet shows that some of these domains end up ethically dubious at best and scams at worst.

It’s pretty easy to determine why so-called “black hat SEO” folks are willing to go through all the trouble: Building a domain from scratch, filling it with high-quality content, waiting for people to link to it, and doing everything by the book takes for-flippin’-ever. Finding a shortcut that shaves months, if not years, off the process and adds the ability to make a quick buck? There will always be people who are willing to go for that sort of thing.

“Google has named inbound links as one of their top three ranking factors,” explained Patrick Stox, a product adviser at Ahrefs. “Content is going to be the most important, but your relevant links will provide a strength metric for them.”

What the spammers are doing

The spammers buy a domain that was recently expired and use a search engine optimization (SEO) tool like Ahrefs to gauge how valuable the site is; it checks how many links are going to the site and how valuable those links are. A link from TechCrunch or the BBC or WhiteHouse.gov would be highly valuable, for example. A link from a random blog post on Medium.com is probably less so.

Once they’ve found and bought a domain, they’ll use something like the WayBack Machine to copy an old version of the site, stick it on a server somewhere, and — voila! — the site is back. Obviously, that’s both trademark and copyright infringement, but if you’re in the market of spamming or scamming, that’s probably the least of your crimes against human decency, never mind the letter of the law.

Over time — sometimes weeks, sometimes months — Google un-sandboxes the domain and is effectively tricked into accepting the domain as the original. Traffic will start picking up, and black-hat SEO wizards are ready for the next phase of their plan: selling stuff or tricking people. There are whole guides for what to do next in order to use these domains, including checking whether there are trademarks registered and redirecting either the full domain or specific pages on the domain using a so-called 301 redirect (“moved permanently”).

“When a site drops off the internet [Google is] just going to drop all the signals from the links. That typically happens anyway when a page expires. Where it’s more complicated is going to be whether any of those signals will come back for a new owner. I don’t think [Google has] ever really answered this in a very clear way,” Stox explained. “But if the same site with the same type of content — or very similar content — comes back, it is more than likely the links are going to start counting again. If you were a site about technology and now suddenly you’re a food blog, all of the previous stuff will likely be ignored.”

As with all things in SEO, however, not everything is cut and dried; it turns out that negative signals continue on expired domains, so it stands to reason that positive signals do, too.

“It’s interesting because sometimes penalties will still carry over, regardless of the content of the new site,” Stox said. “So certain things may still factor in. There’s a giant list of Google penalties — such as backlink spam, content spam, paid links, etc. They can carry on to the new site, and sometimes people will buy … an expired domain and put a new site up. Nothing is ranking, and on closer inspection, they’ll find a penalty set in inside Google Search Console.”

Sullivan reassured us that the search engine giant knows what’s going on and that it has a handle on things.

“It’s not just fair to say that all purchased sites are spam and that they, therefore, should be treated as spam,” said Sullivan, pointing out that the company’s robust spam filters are there to protect searchers. “When actual spam happens, we have a whole ton of spam-fighting systems we have in place. There are millions and millions, if not hundreds of millions of [pages and sites] that we’re constantly keeping out of the top search results. One metaphor I like to use for people to understand just how much work we do on spam is this: If you go into your email spam folder, you go, ‘Wow, I didn’t see all these emails.’ That is stuff that existed but didn’t show up because your system said, ‘No, this isn’t really relevant for you. This is spam.’ That’s what’s happening on search all the time. If we didn’t have robust spam filters in place, our search results would look like what you see in your spam folder. There’s so much spam and our systems are in place to catch it.”

There’s no doubt that Google does a lot to defend us from spam, and yet there’s a thriving industry for high-value expired domains that are available, whether for honest attempts at corner-cutting or more nefarious deeds.

A thriving industry

You don’t have to dig very deep to find examples of domains that, at first glance, look legitimate, but that have been sneakily shifted to another purpose. Here are a few I came across.

One example is the Paid Leave Project, which used to live on paidleaveproject.org, but moved its site to USpaidleave.org at some point. Unfortunately, someone at the org didn’t renew and/or redirect the old domain, and the site that used to work hard to ensure that workers in the U.S. can get paid family leave is now, well … helping families grow in different ways:

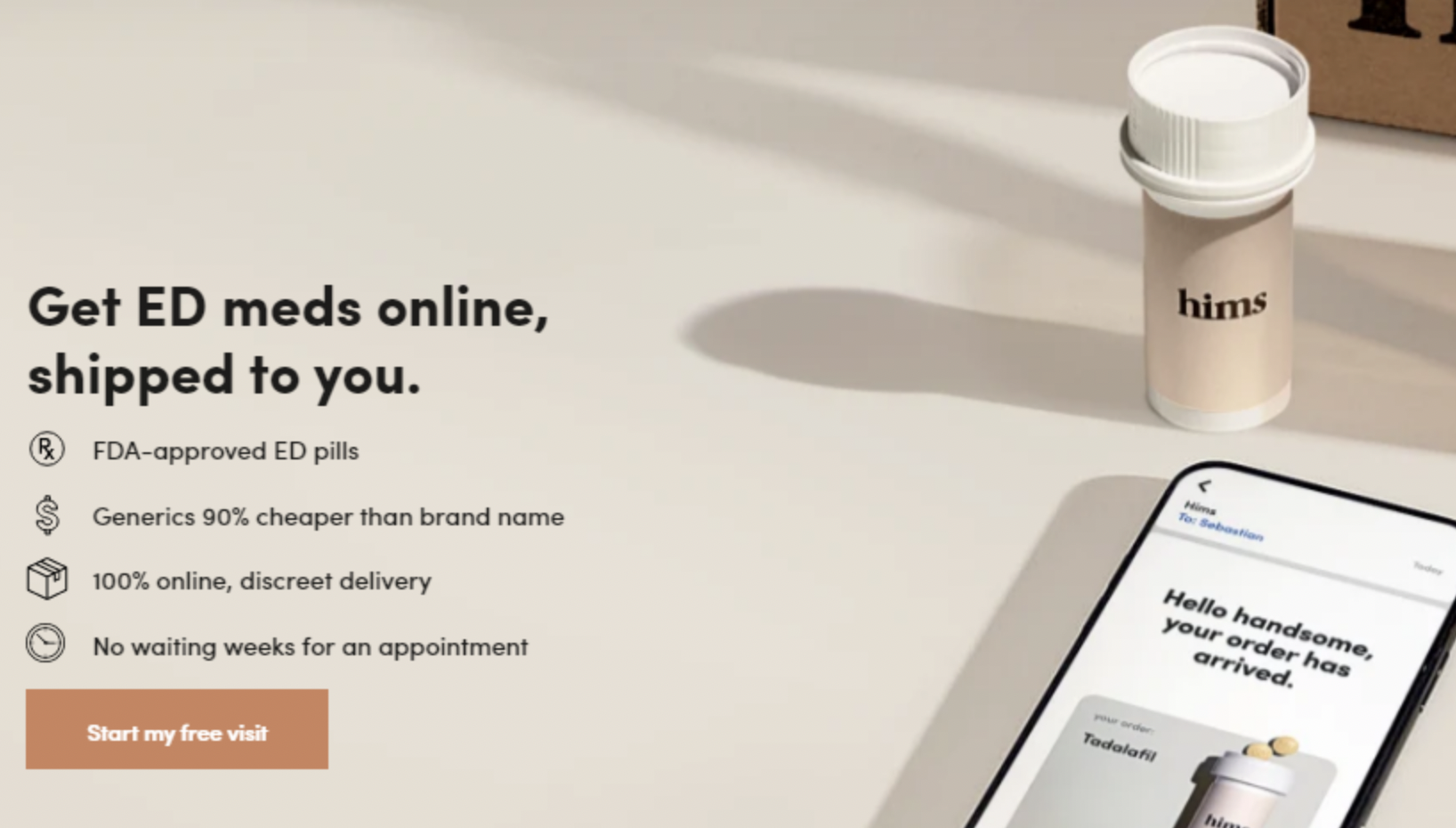

A screenshot of paidleaveproject.org, which now appears to be some sort of affiliate site for erectile dysfunction pills.

Another tragic story is Genome Mag, which ran from 2013 to 2016, expired, and then came back online as a different magazine that the original owner doesn’t have control over.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·