One of the trickiest parts of this gig is setting realistic expectations. The job of writing about robots for a living is a bit of a balancing act between excited optimism and pragmatic realism. How do you temper the excitement of some of the world’s most fascinating technologies with reality’s inevitable encroachment?

Covering robots in various capacities for over a decade now has taught me the importance of keeping one’s powder dry. You want exciting headlines that will draw readers in and give the work the coverage it deservers without overpromising. People will accept your hyperbole for only so long.

For me, the lesson was learned on a visit to a university research lab 5 to 10 years back. Robotics professors largely develop realistic timelines when it comes to the real-world deployment of early-stage technologies. I was regularly told that such applications were for 5 to 10 years out. Having waited through it, it’s exciting to see so many of them enter real-world usage. Matured technologies and a global pandemic dovetailed perfectly to deliver on so much of robotics’ promises.

Image Credits: Bear Robotics

However, pragmatism means reporting the bad along with the good. In recent weeks, that’s meant a number of firms reacting to broader market trends, through layoffs or closures. It also means checking in on earlier reports of progress. Take this week’s Chili’s financial reports via Restaurant Business that found the fast-casual restaurant chain hitting the big, red pause button on its deployment of Bear Robotics serving robot, Rita.

“The robotics project we’re pausing right now,” said Kevin Hochman, who stepped into the CEO role at Chili’s parent, Brinker, in May. “We’re going to stop some of those projects that we just didn’t have a line of sight to a return on the business. But we’re going to double down and accelerate the ones that we think will have a more meaningful impact on restaurant margins and a quicker impact on our business.”

ROI is a tricky thing to calculate with these sorts of pilots, of course. And I think the bigger question with this specific sort of technology is how much it can directly address staff shortages plaguing restaurants — and virtually every other service sector at this point. It’s a setback for sure, particularly after Chili’s agreed to bring the ’bots to around 60 locations, just before the start of Hochman’s tenure.

We’ve reached out to Bear Robotics for comment.

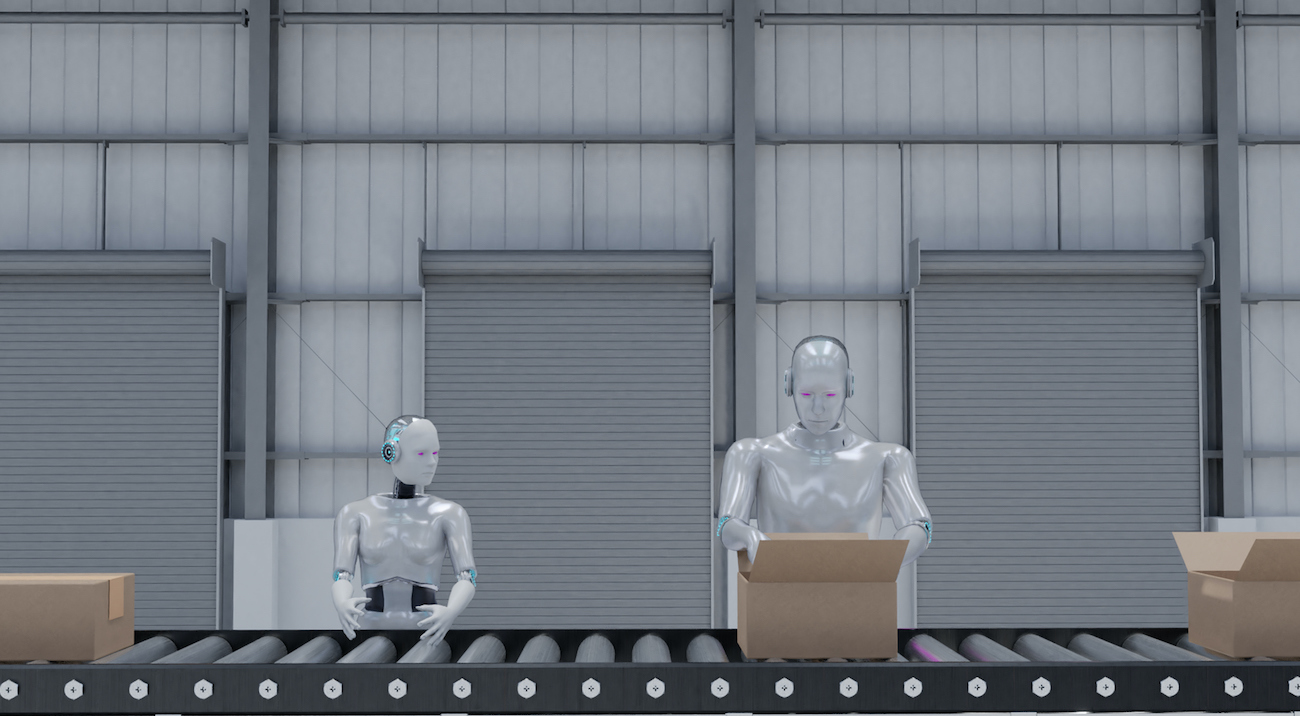

Image Credits: Ekkasit919 / Getty Images

If you’ve followed my work in the space, you know that automation’s impact on labor has been an important topic. For that reason, I wanted to draw attention to this report from the University of Central Florida, which puts the conversation in an interesting context that’s too often ignored. The study looked at public reaction to automation in European countries that have different levels of wealth inequality.

“Countries that have more people in unequal standing, on average, tend to see these technologies more as a threat,” UCF professor and the study’s co-author, Mindy Shoss, says. “The U.S. always ranks pretty high on inequality and societal inequality. Given that, I would suspect that there probably are, on average, similar negative views of AI and robot technology in the U.S.”

It’s the sort of thing that seems obvious on the face of it, but probably isn’t being discussed enough. People are smart, and they implicitly understand that a push toward greater automation in society risks disproportionately impacting blue-collar workers. Let’s face it, these are the first jobs to be automated, and doing so will likely contribute to an already expanding wealth gap.

These are precisely the sorts of conversations we need to be having any time we discuss wide-scale automation. The roboticist long tail view tends to be very rosy about this stuff, but the people directly impacted by such innovations deserve a place in the conversation as well.

Shoss adds, “There’s a lot of potential of these technologies to help make work better by doing dangerous tasks or giving people more flexibility, but there’s also some risk involved in these technologies. And the implication from our research is that if you’re going to try to develop robots or AI technology in a highly unequal society, there might be more barriers to getting people to adopt that kind of technology.”

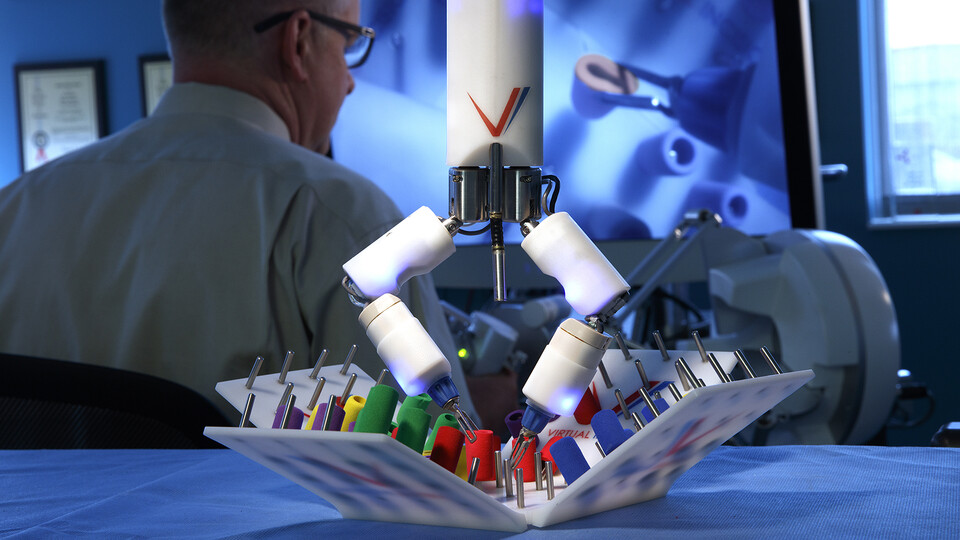

Shane Farritor, Virtual Incision surgical robot photographed in the group’s Nebraska Innovation Center office and lab. April 11, 2019. Image Credits: Craig Chandler / University Communication.

All right, on to the fun stuff. I missed this earlier in the month, but it still warrants a spot in Actuator. NASA has awarded the University of Nebraska–Lincoln $100,000 to bring a surgical robot into orbit as part of a 2024 ISS mission.

The ability to perform remote surgery has some very clear advantages for space exploration. The robot’s inventor, Shane Farritor, notes, “The astronaut flips a switch, the process starts and the robot does its work by itself. Two hours later, the astronaut switches it off and it’s done.”

Image Credits: Miko

(opens in a new window)

As we’ve seen from companies like Sphero and littleBits, Disney Accelerator’s backing can be something of a mixed bag. Though, having such valuable IP at your disposal definitely feels like a plus. This week, Miko announced that its little kids robot, Miko 3, is getting access to animated storybooks featuring characters from films like “Moana,” “Frozen,” and “The Lion King.”

“Bringing the imaginative worlds of Disney and Pixar to our platform represents a big step in kids robotics,” Miko cofounder and CEO, Sneh Vaswani, told TechCrunch. “Miko is thrilled to be the first robotics platform to have such an innovative collaboration with Disney, and we look forward to raising the benchmark for kids engagement together.”

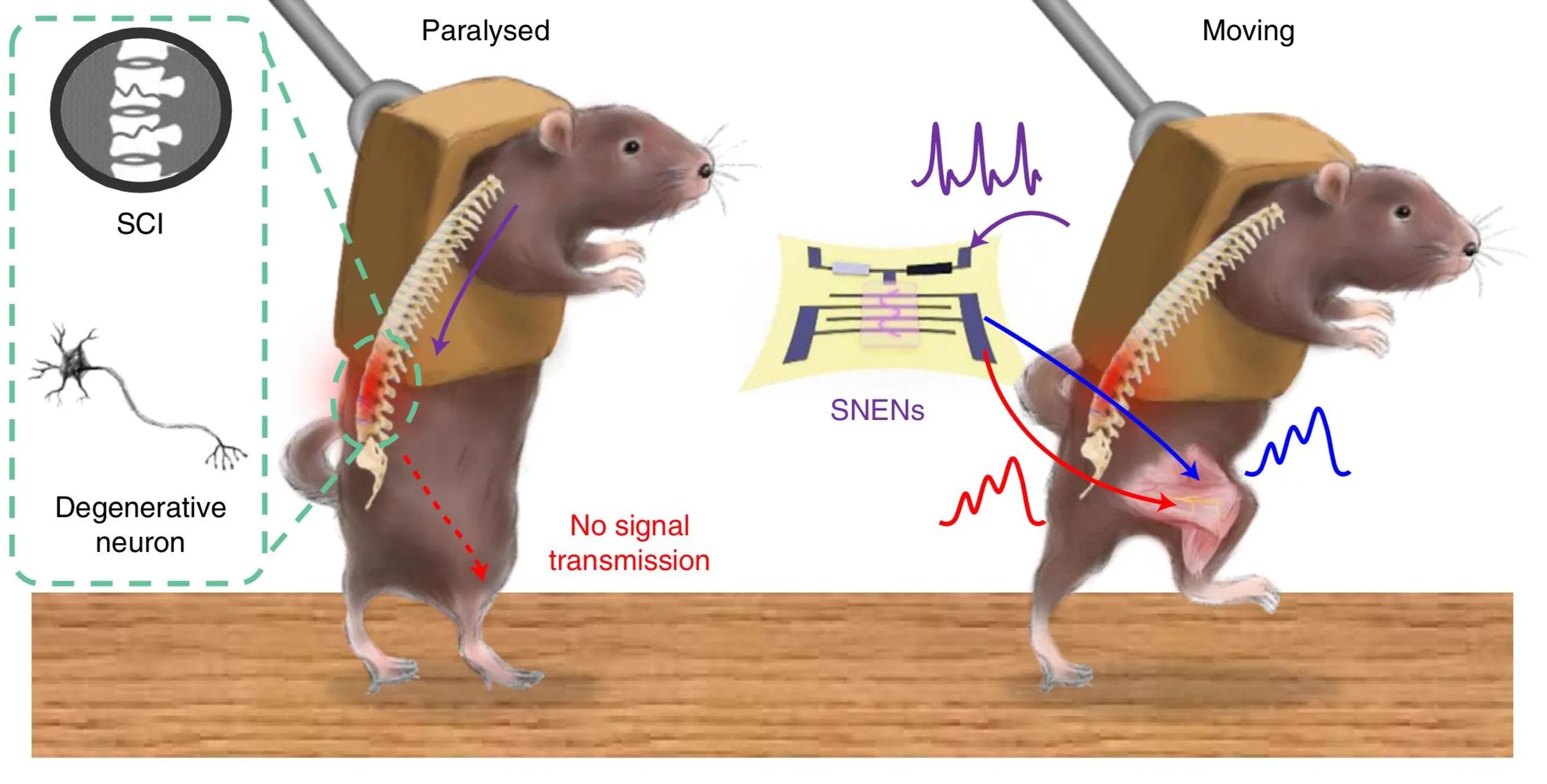

Image Credits: Stanford University

And lastly, some research from Stanford and Seoul National University, by way of IEEE. The schools are highlighting work around artificial nerves capable of helping paralyzed mice run.

“Our work is the first example of delivering biological neural signals through biomimetic electronic nerves to biological organs,” the paper’s senior coauthor Tae-Woo Lee notes. “Through this, it seems possible to present new solutions and strategies for nerve damage in humans such as spinal-cord injury, peripheral nerve damage, and neurological damage such as Lou Gehrig’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s disease.”

The hope, of course, is to one day develop similar results in human patients.

Image Credits: Bryce Durbin/TechCrunch

Subscribe to Actuator, for all the good and bad robotics news.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·