I’m not a branding expert. I can recognize, however, that one sets certain expectations by naming a product “Happy Ring.” Mental health is a delicate space, and not something to be taken lightly. As a rule, it’s best to avoid anything that promises to fix you without the requisite talk therapy and, perhaps, medication. No wearable is going to replace that — certainly not during our lifetimes.

Nor, of course, can a consumer device diagnose conditions. While doctors are increasingly recommending products like the Apple Watch to consumers, they’re best regarded a proxy for monitoring one’s vitals all the time we’re not at the doctor’s office.

Ultimately, I don’t think the Happy Ring name does its creators’ ambitions justice. It at once evokes the 70s mood ring fad, while suggesting that the product is punching above its weight in terms of its ability to create a profound transformation in the person who wears it. It’s a disservice, because there’s obviously something to the notion that our emotional states have physical manifestations in our body.

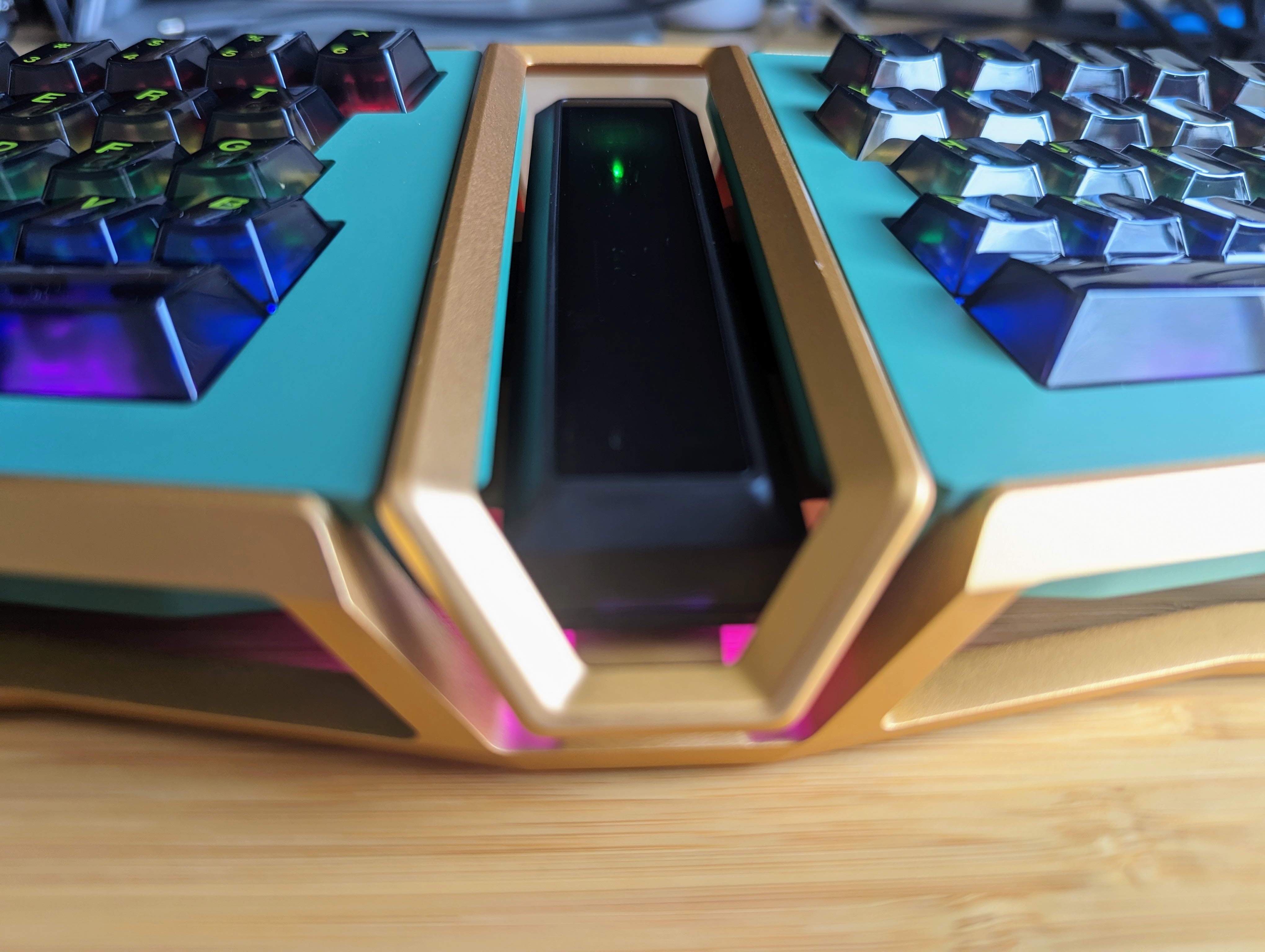

Image Credits: Happy Health

It’s something a lot of wearable companies are clearly working toward. Take a look, for example, at this internal Oura study, which attempts to answer the question of whether the ring can “help identify symptoms of depression and anxiety.” There’s also this report that finds Apple working with UCLA in an attempt to attempt to use its consumer devices to help identify conditions like anxiety, depression and cognitive decline.

Mental health is, understandably, a kind of wearable holy grail. Listen, it’s real tough out there right now. Who wouldn’t want to just pop on a ring to get a clearer picture of their mental health? Mental health is big, scary and inscrutable, and traditional methods of addressing it can seem insurmountable.

Happy Ring makes no claims of being a diagnostic tool. Rather, the company believes it has cracked the code of monitoring wearers’ progress, in a kind of mental health analog to fitness trackers like Apple Watch and Oura. Much like those products, it purports to be a method for monitoring those vital readings and presenting actionable data to help get the wearer back on track.

Image Credits: Happy Health

Tinder founder Sean Rad tells TechCrunch he teamed with LVL Technologies founder Dustin Freckleton to determine whether a wearable device can present an accurate picture of its wearer’s mood.

“There were all of these wearables that helped you understand your physical fitness or sleep,” says Rad. “But they were really ignoring the elephant, which is your mind. They weren’t doing anything when it came to mental health or mental states. We asked the question: can we somehow build a device that can passively start to monitor what’s going on in your brain? If we can do that, can we help people better understand, have the language and better identify what they can do to improve their mental health?”

In addition to the standard array of wearable sensors, the startup points to a custom-built EDA (electrodermal activity) detector as the product’s hardware differentiator. Fitbit announced its own version of the technology a few years back, as a method for detecting the wearer’s stress levels. Addressing “stress” versus “mental health” with a wearable seems like a more reasonable ask.

“If you’re public speaking, you’re going on a first date, you’re interviewing for a job, you hands start to sweat a little bit,” explains Freckleton. “That is the emotional sweat response. There are evolutionary reasons why that occurs. The EDA sensor is specifically designed to pick up those tiny changes that occur as a result of micro sweats on the skin and are a result of the activation of the autonomic nervous system.”

Image Credits: Happy Health

Founded in late-2019, Happy Health currently employs 40, 13 of whom are located in Austin, where the startup is headquartered. The firm also just announced a $60 million Series A, led by ARCH Venture Partners.

“Funding went to research development and manufacturing of, really, a best in class wearable device,” says Freckleton. “There’s no comparable device from a sensor level to data quality level to AI infrastructure level.”

The preorder waitlist for the product opens today. The company is offering a hardware-as-a-service model, straight out of the gate. There’s no upfront cost for the hardware, with plans starting at $20 a month. That includes things like sleep analysis, heart rate monitoring and journal prompts. Mindfulness content is limited. Happy says it’s not specifically looking to enter that already crowded market, and is instead exploring potential partnerships with third parties.

Image Credits: Happy Health

There is, however, an actionable aspect to the connect app, as well as an attempt to chart how your mental health changes over time.

“Every metric we’re giving you on your mind is actually real time,” says Rad. “So you could literally do something, open the app and see the result right away. But we also give you CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) exercises, breathing exercises, meditation, educational pieces — different things that are tailored to help you improve.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·