It was the world’s largest gathering of internet celebrities. As I waited to meet Twitch streamer Code Miko in a hotel lobby at VidCon, I spotted an Instagram-famous husky, a fan favorite contestant from Netflix’s “The Circle,” and a controversial beauty blogger. But when a fashionable Korean American woman approached me, I realized I was half expecting to see a 3D, hyperrealistic animation in front of me, rather than a real human. Maybe it was the near-hallucinatory exhaustion from day three of a massive online video convention, but unlike so many of the social media stars in the echoing hotel entrance hall, VTubers like Code Miko are sometimes unrecognizable in person.

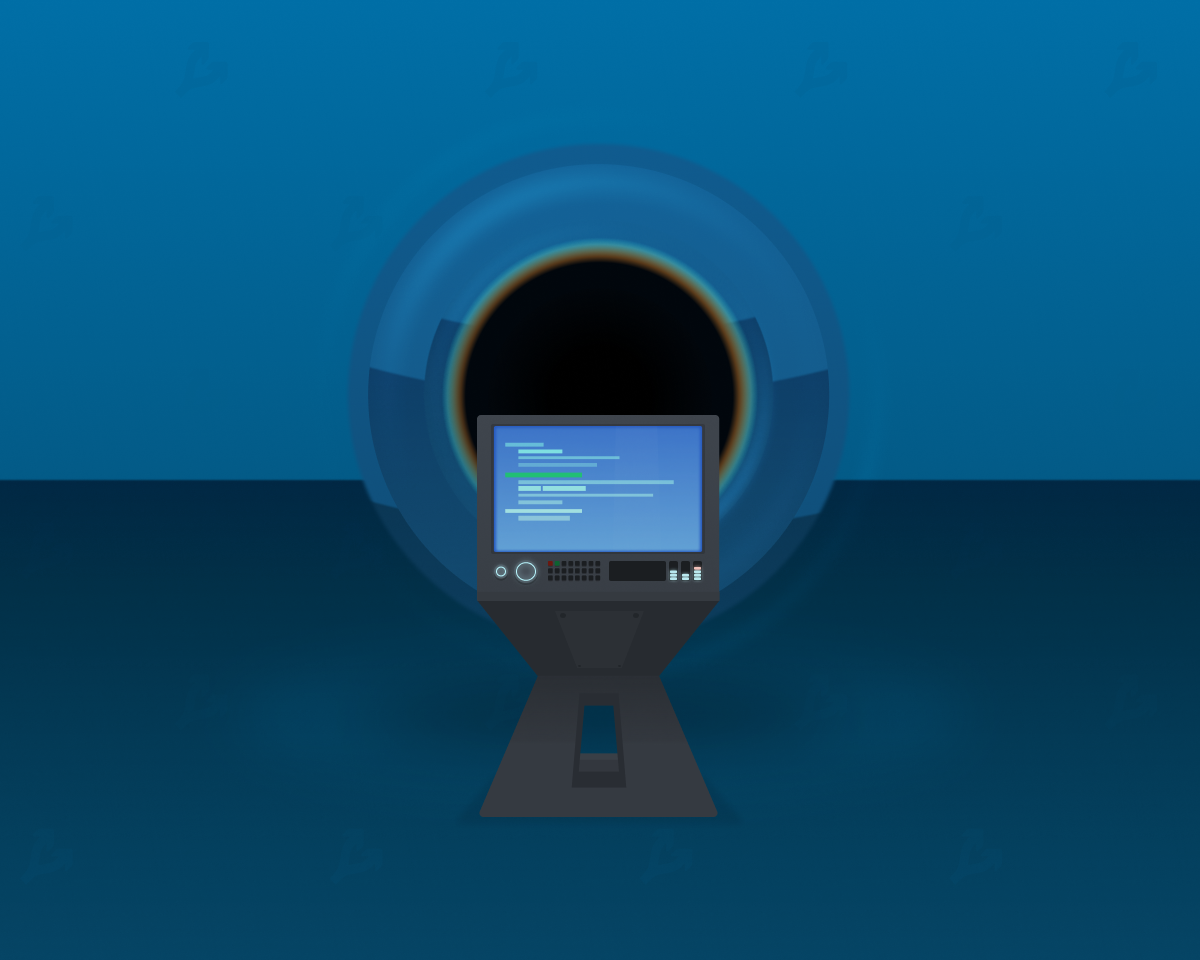

A movement originating in Japan, “VTuber” means “virtual YouTuber,” but the culture is also prevalent on other streaming sites like Twitch, where Code Miko has almost a million followers. To build their virtual personas, streamers use motion-capture (or even just AR face-tracking) technology to embody a virtual avatar and weave a backstory and mythos around the character.

“I thought it would be really fun to be another character,” the streamer told TechCrunch. “I just felt like I had this vision. I wanted to take control of a virtual character and have the audience be able to interact with her live on stream. I’m a big fan of ‘Ready Player One,’ so when I felt like I could make a tiny percent of it, I was really excited.”

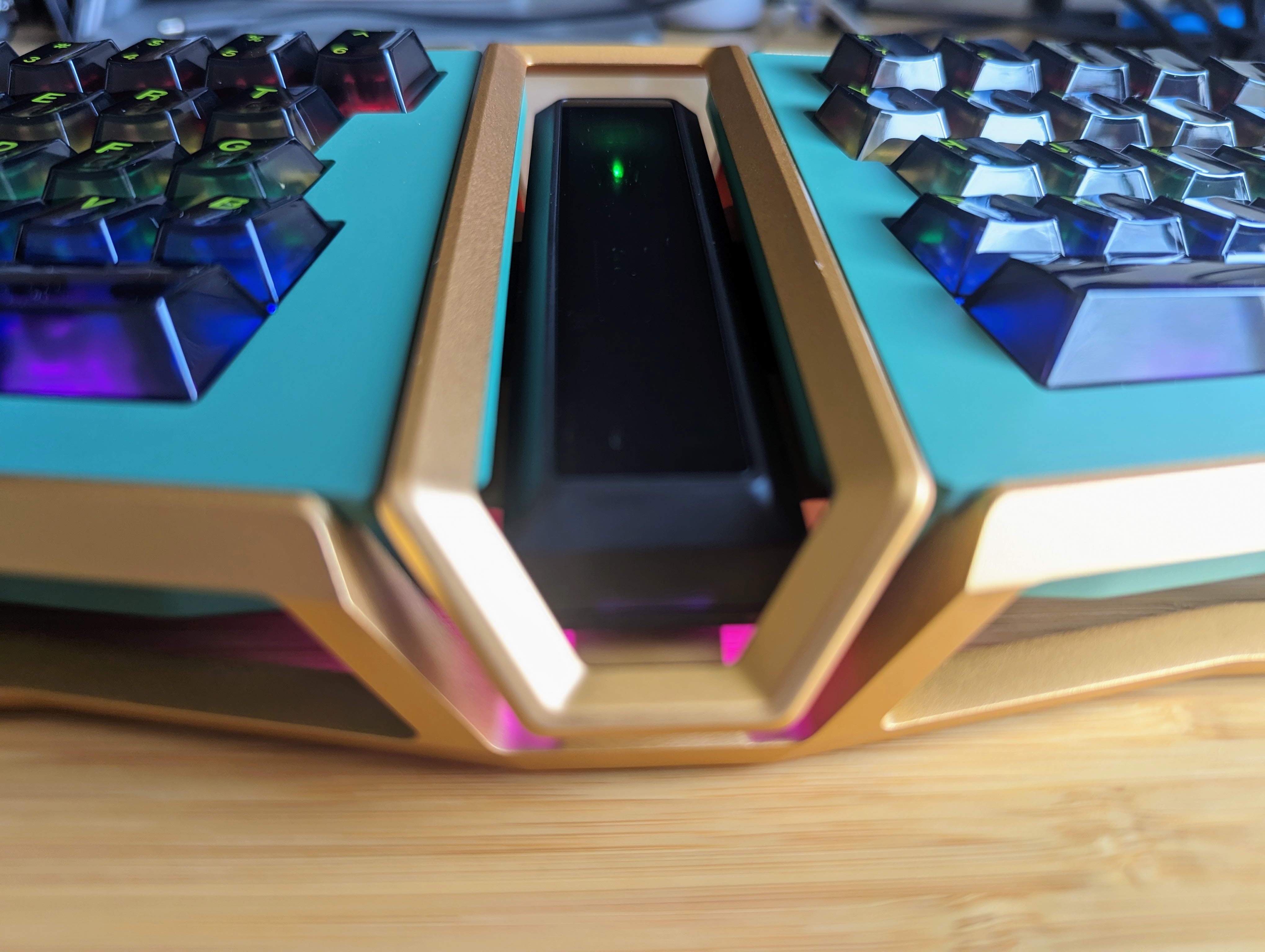

The Code Miko character, for instance, is an NPC (non-playable character) who dreams of starring in a major video game, but she’s too glitchy, so she’s resorted to streaming instead. Fans call the actual human behind the avatar “the Technician,” but her first name is Yuna. Since Yuna was a VR animator before she was laid off in the pandemic and created Code Miko — which is now her full-time job — her avatar is far more realistic than most VTubers. Also, most VTubers would never dare meet a journalist in person, let alone show their face on stream. But Yuna sometimes shows her face to offer viewers a behind-the-scenes peek at her mocap technology.

VTuber avatars usually resemble anime characters, since the genre first emerged in Japan. Fans disagree about who the first VTuber was — some say that the culture was sparked by Hatsune Miku, the avatar of a Vocaloid music production software who has opened for Lady Gaga, appeared on David Letterman, and performs live for stadium-sized audiences. Others credit Kizuna AI, a project of Japanese tech company Activ8, who started her channel in 2016 and coined the term “VTuber.”

Kizuna AI’s popularity birthed a new generation of online stars in Japan. Unlike Japanese idol culture, which holds its real-world celebrities to impossibly high standards, VTubers are more free to be themselves, even though they’re performing as a virtual character.

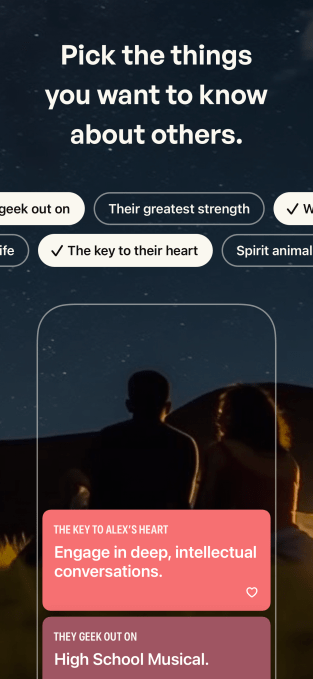

“They exist in this space between anime character and real person,” said anime YouTuber Gigguk in a video. “But they can explore original ideas or get away with things that other people can’t who exist in the same space.”

VTubers thrived for years in Japan, but the genre turned heads around the world during the pandemic. As much of the world entered lockdown, the massively popular VTuber agency HoloLive launched its English-language division, courting a new audience of Western viewers.

The plan didn’t just work. It changed the landscape of streaming forever.

In just two years, HoloLive English’s most popular VTuber Gawr Gura has amassed over 4 million YouTube subscribers. The white-haired anime girl wears an oversized, blue shark hoodie, her face framed by the hoodie’s shark teeth. Of course, her bright blue eyes are the same color as the highlights in her hair, and when she smiles, her adorable shark-like teeth peek out. She’s a musical artist, as many VTubers are, and she streams games like Minecraft, Mario Kart and even Japanese Duolingo. According to her channel description, she is “a descendant of the Lost City of Atlantis, who swam to Earth while saying, ‘It’s so boring down there LOLOLOL!'”

At the same time, HoloLive also introduced talent like Mori Calliope (2 million subscribers), who claims to be “the Grim Reaper’s first apprentice” and became a VTuber to “collect souls” from her viewers. Calliope is a red-eyed rebel, adorning her pastel pink hair with a black crown and veil.

We can’t confirm the progress of her soul-harvesting, but when it comes to money, Calliope is certainly succeeding. According to Playboard, an independent YouTube analytics site, Calliope earned $854,595 in 2021 just from superchats (a YouTube livestream monetization feature), making her the seventh-most superchatted YouTuber in the world.

Who were the six streamers who out-earned Calliope’s superchats? Also VTubers, of course.

Why become a VTuber anyway?

It’s rare for a VTuber to reveal their human body like Code Miko — for many of these streamers, the anonymity is the whole point.

You don’t have to sign to a major agency like HoloLive to become a VTuber. Though Code Miko’s technology is ultra-advanced and puts Mark Zuckerberg’s metaverse to shame, it’s not the norm. With only an iPhone, a new streamer can create a face-tracked, 2D virtual persona.

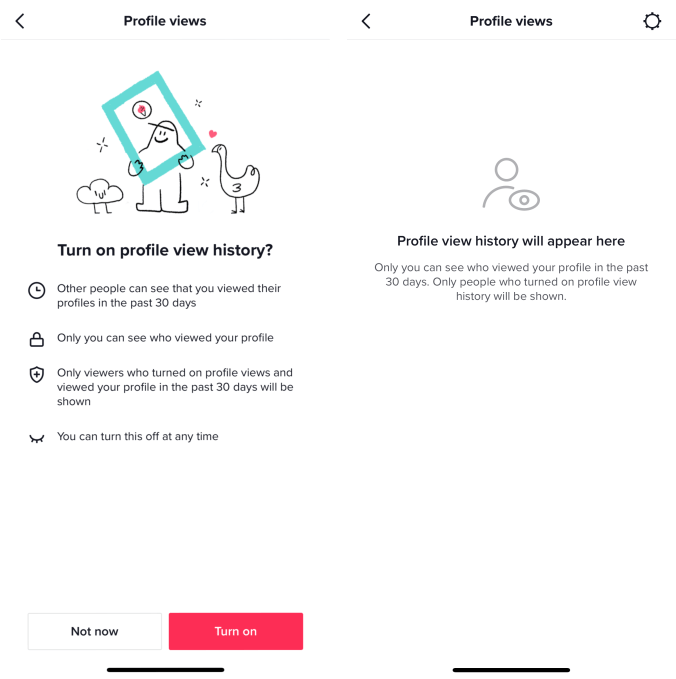

Now, there’s a growing community of trans VTubers, some of whom say that adopting an avatar has helped them navigate gender dysphoria. Unlike the TikTok side of social media, where showing your face is almost non-negotiable, VTubers can show another side of themselves screen. VTuber Ironmouse, for example, is the most-subscribed female streamer on Twitch. But in real life, the Puerto Rican gamer is chronically ill and sometimes bed-ridden, so VTubing helps her have fun and socialize, especially when isolating from the coronavirus.

For some streamers, these avatars are also barriers against harassment.

“I don’t get the same amount of bad treatment online as my female coworkers do,” Yuna told TechCrunch. “It’s harder to troll somebody that’s a cartoon.”

Then again, in a recent stream where she showed off her state-of-the-art mocap suit, she called out a viewer for commenting that her technology was “the future of porn.” While some VTubers do get a bit racy — it is the internet, after all — there’s more to these digital personas than sex appeal.

“I think for people who watch VTubers, a lot of them don’t even care about who is behind the avatar, who is the voice actor,” explained Zhicong Lu, an assistant professor at the City University of Hong Kong who has studied VTubers. “It’s more about the persona, the avatar, and they know very little about the real life of that voice actor.”

Anonymity creates its own set of new challenges, though.

“Especially for VTubers run by companies, the voice actors may be replaced, and their labor may be exploited,” Lu said. Many of the most popular VTubers are created or managed by agencies like HoloLive, Nijisanji and VShojo. VTubers have distinct personalities informed by their voice actors, but it’s possible for agencies to bring on a new voice actor without fans noticing. Plus, it’s not public knowledge what the percentage of pay the talent gets from the agency.

“The tricky thing is, people actually cannot see anything,” Lu told TechCrunch. “It’s totally opaque. It’s not transparent, because of the avatar.”

Of course, corporations want to cash in

In mid-August, a VTuber of Tony the Tiger made his streaming debut as part of a partnership with Twitch. Yes, that Tony the Tiger, the Kellogg’s Frosted Flakes mascot who has appeared on cereal boxes since 1952.

Image Credits: Kellogg’s (opens in a new window)

A marketing and VTubing expert, Teddy Cambosa told TechCrunch that brands like Netflix, SEGA and AirAsia have used VTubers in their marketing. But activating the massive fanbase around VTubers isn’t so easy as simply participating.

“Brands need to better understand that tapping into the VTuber space need to understand that the demographic is not just for the short-term period,” Cambosa said. “Once they understand the culture and behavior of these fans, they can tap into the fan’s loyalty in order to acquire them as potential customers and retain them in the longer run.”

Tony the Tiger’s VTuber debut was awkward. The mascot did not actually play “Fall Guys” along with the four IRL streamers who joined him, and he left the stream for long stretches of time, prompting thousands of viewers to demand Tony’s return in the Twitch chat. He made up for his absence a little bit, though — Tony the Tiger told his 13,000 viewers that they are his “pog champs.”

Beyond the VTuber space, brands like Pacsun and Calvin Klein have partnered with Lil Miquela, a completely fictional Instagram influencer who is operated by a venture-backed company called Brud. But these advertising campaigns are often met with backlash — why not partner with a real, non-CGI woman to model these clothes? Social media is already criticized for harming teen girls, in part by promoting unrealistic beauty standards. But no beauty standard is as unrealistic as a virtual ideal of a female body.

Tony the Tiger and Lil Miquela have the technology and the financial backing to be technically impressive and well-marketed, but VTubers have to be authentic to connect with fans. Even for VTubers who only connect with audiences through their avatars, the phenomenon is ultimately about the human connection. After all, there’s still a real human behind those big anime eyes — even if you’ll never see their face.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·