WorkWhile co-founder Jarah Euston isn’t alone in her mission of connecting workers to flexible, reliable work. Where she does stand out, though, is her belief that many labor marketplaces today are built atop a fallacy.

“I never subscribe to this notion that what workers want is infinite flexibility,” she said in an interview with TechCrunch. “That probably comes from people who have not tried to pay their rent working an hourly job, not having the visibility and guarantee that you’re going to make enough to pay your bill.”

She added: “Workers need flexible schedules, they don’t want infinite flexibility…the idea that somebody wants to be an Uber driver and drive for 30 minutes and then go sit on the beach for three hours and then drive for ten more minutes is a fallacy that the market has told itself.”

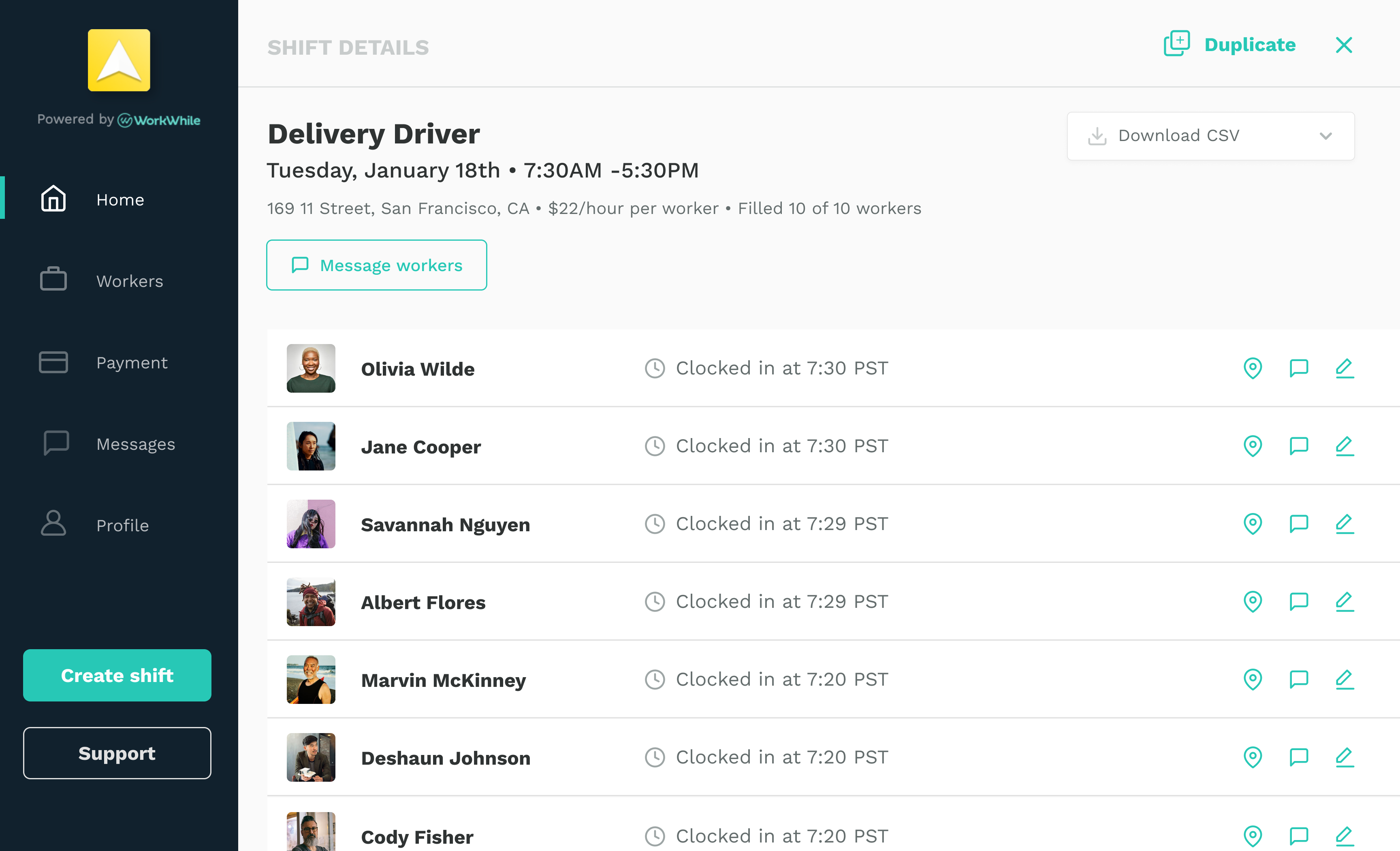

The absence of a platform that helps workers understand what they’re getting, and how often they’ll be able to get it, seeded Euston’s interest in launching WorkWhile alongside co-founder Amol Jain. Founded in 2019, WorkWhile connects hourly workers to open shifts, as well as benefits such as next-day pay, access to telehealth services, and pay transparency.

WorkWhile is live in 13 markets, including where it’s based, in the San Francisco Bay Area, as well as Los Angeles, Atlanta, Miami, Northern New Jersey, Atlanta, Seattle, Houston and NYC Metro. The growth, alongside Euston’s vision, has attracted some significant investor interest.

The startup announced today that it recently raised a $13 million Series A, led by Reach Capital with participation from existing investors including Khosla Ventures, F7 Ventures and new investors including Chamaeleon, Position Ventures and Gaingels.

Ultimately, the moonshot of WorkWhile is that it can build a marketplace with a stickier worker, one who turns to it not only for shifts, but also for standing support and services (regardless of what their work week looks like). Runner, founded by Arlan Hamilton, recently launched with a similar take: it hires part-time, on-demand workers as W-2 employees for more job stability, and then connects them to jobs in tech operations. Bluecrew does a similar service, but employs folks before connecting them to roles in bartending, event management, security, data entry or customer support.

The rise of interest in stable, flexible jobs could partially be a reaction to the Great Resignation, but also just a further signal that the freelance economy has matured to the point that even workers who seek atypical jobs want support. WorkWhile says it has filled shifts at companies like Advance Auto Parts, Ollie’s Bargain Outlet, Good Eggs, Thistle, Edible Arrangements, Dandelion Chocolate and Bassett Furniture.

Image Credits: WorkWhile

Euston said that 80% of workers on WorkWhile’s platform are looking to work more than 30 hours a week, while 60% want 40 or more hours a week. “We don’t ever use the word ‘gig’ at Workwhile. We don’t want to be viewed as a gig platform,” Euston said. “We want to be viewed as the best place to earn a stable paycheck.”

Adding onto its pitch to be worker friendly, WorkWhile doesn’t charge workers a dime to use its service. Instead, it makes money by charging businesses that use it a percent fee based on the rate paid to the worker. What’s in it for the employers, of course, is the promise of a more reliable workforce that doesn’t turn over as fast.

Euston said the company is all about finding data points to signal “how people feel about work” and then creating profiles around it. For example, when a worker first onboards to WorkWhile they do an orientation, followed by a behavioral test.

“It’s not hard, but it’s really a test of follow through,” she said. “We’re asking about attitudes around the workplace, like how many times in a year do you call out sick, and how many times a year do you think other people call out sick?” WorkWhile’s current no-show rate is only 5%, it has a 76% accuracy in predicting if a scheduled worker will attend a shift.

The challenge by tracking data points in this way is it can disproportionately weigh against historically overlooked individuals, or folks with a lower socioeconomic background. Ultimately, the startup isn’t for folks looking for flexible work in a primarily part-time capacity, which could take out entire cohorts of the market. Another interesting data point? About 28% of hourly workers on WorkWhile platform own crypto.

Euston said that they “very intentionally” do not ask any demographic questions in the app, and do not include age as a factor in their predictive modeling based on aforementioned reasons. Based on optional worker surveys, WorkWhile says that 80% of users identify as POC.

“Our philosophy with the models is to manage risk, rather than prevent folks from working. For example, if we predict someone has a less than 50% chance of showing up to a shift, we may send an extra backup worker to make sure the customer’s request is met,” she added. “If our model was wrong and everyone shows up, the backup worker still gets paid but the customer is not charged.”

The company claims it doesn’t restrict anyone from attempting to work, but does offer the first opportunity of new shifts to those with higher ratings. “In the future we also imagine building more support for those who we predict may have trouble getting to the job site[…] if we know you don’t have a car, we could consider showing carpool options,” she said.

Image Credits: WorkWhile

English (US) ·

English (US) ·